Mentorship

The images we have in our minds about the concept and role of mentorship can span a multitude of assumptions and expectations. From figures of authority to figures of intimacy, mentorship is a relation that can take many forms...

When I say 'mentor' can you give me another image or figure? What do you think of? Who do you think of? Out of the blue, I ask a friend these questions in a series of text messages. 'Supportive Listener' and 'Critical Friend', she replies. Then, after a few minutes, she adds: 'Someone who thinks in parallel to you. It's a kind of spatial relationship with someone who doesn't always know more, but knows differently and from a different angle...'

This friend of mine is a mentor to me. I don't always draw on her for help in this way, but even knowing she's out there, somewhere in the world, doing her thing... this gives me courage. Asking for her point of view is a way for me to think back to myself about what I'm trying to do or about how I feel or think about my experience. I think the idea that a mentorship relationship is one where each person lives in parallel, yet somehow in conversation with others, is beautiful. Implicated but not tethered. My friend spelled this out for me. And even though this relationship is a tricky thing to describe, Linda Ryan, the EDGE training and development coordinator, is spelling it out everyday in her work.

The mentorship relationship reflects an ability to improvise, to be present with others, to listen, to be vulnerable, to care, share ideas, emotions, knowledge and experience.

Working with Linda has been one of the joys of engaging with the EDGE program. Her passion for interpersonal communication, relationship and wellbeing has led to her casting a spell over the interdisciplinary worlds of information and communication technology research. A spell that, in the same spirit as Stranger Fictions, invites us to open up ideas, assumptions, mythologies and expectations of our research relationships, giving us a chance to actively explore our capacity for mentorship, both as givers and receivers. But Linda got the sense that many of her colleagues did not share her practical philosophy of mentorship: “I'm just so curious as to why somebody would go, 'nah, no. All that advantageous conversation for me? No. I don't want it.' So I 'd just be so curious to learn whats behind a persons thinking.” The word 'mentorship' can refer to a broad reality of relations that are often taken for granted. We saw that this word could really benefit from some collective and critical consideration through the forum of Stranger Fictions.

For one of our earliest conversations to tease out the misunderstood qualities of mentorship, Linda and I walked to Merrion Square, a park close to where the EDGE management team are based, at Dunlop Oriel House near Dublin's city centre. It was very sunny, a little too hot to sit out perhaps, for ones with pale skin. We sat on the wall, in the raised courtyard at the edge of the park, just near the entrance. All the benches were occupied by one body each. So we perched on the wall, facing the railings and the sun. A man offered his bench to us and went to sit with another body on another bench, who turned out to be his partner. They must have needed some space. That was, in a way, what we were meeting to talk about: the to and fro of relationships. Being together, being apart, holding open companionable, critical, creative, intellectual, and embodied relationships. In the interdisciplinary space of information and communication technology research, what does mentorship look like? Not everyone understands, Linda told me, what this relationship means and why it might be of value. It's so difficult to put relationships into words. You have to act them out to tell them, to change them, to make new forms and patterns of relationship. Sometimes its just as simple as meeting someone for a coffee and talking at random about things that are happening for you. And the great thing about this relationship is that you can walk away and there are no strings attached, it's not tit-for-tat in that direct way. All the benefits are indirect, intangible. But they're there. And they're so valuable.

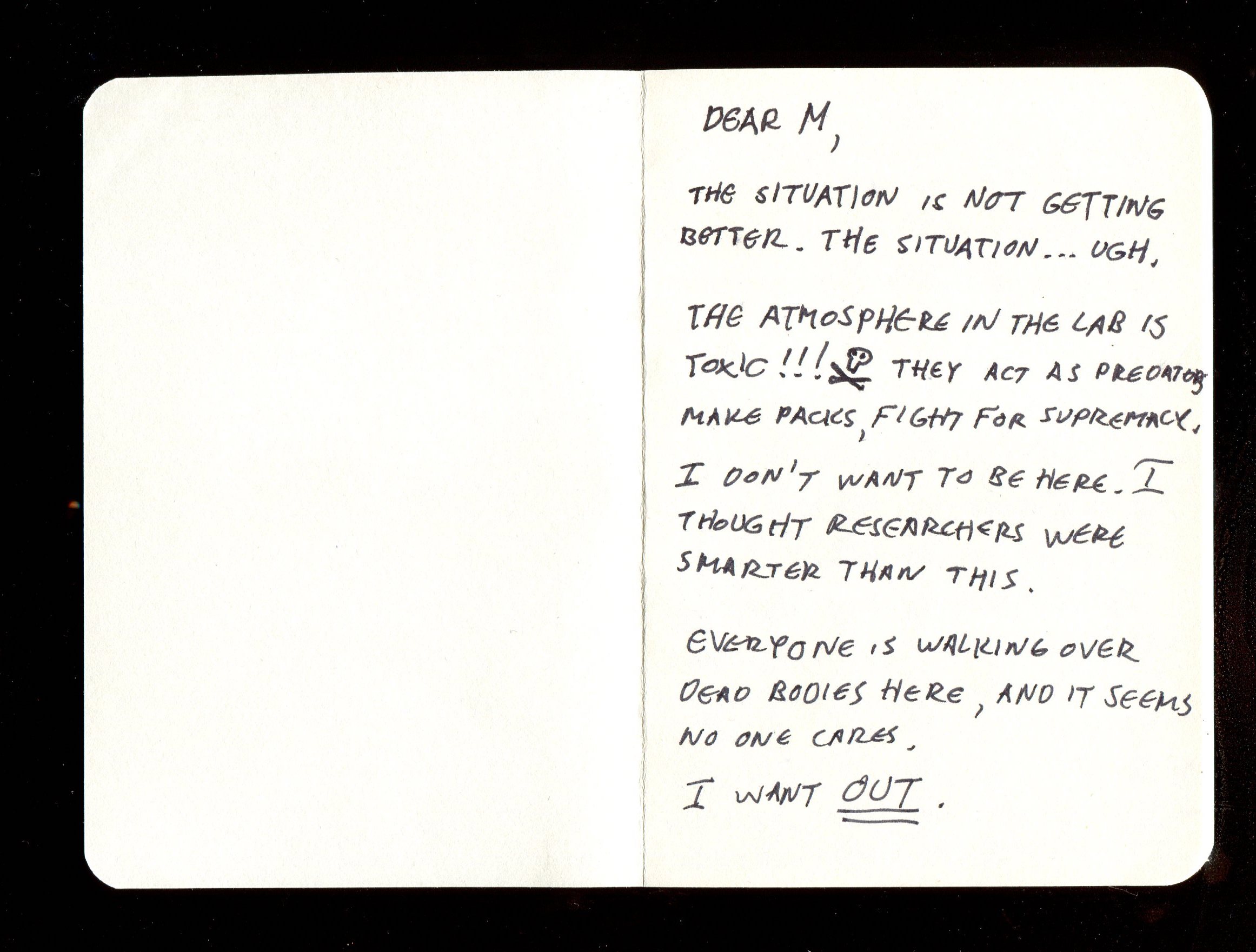

Linda could tell that her concept of mentorship was in many ways at odds with a Status Quo understanding of mentor/mentee relations in academic research, particularly in the space of information and communications technology research. What she often witnessed amongst her colleagues was a living tradition of hierarchical power-relations between Principle Investigators/Supervisors, Post-Doctoral researchers and Ph.D students that could sometimes foster cultures of competition, insecurity, fear and, for many, isolation. This was at odds with the kinds of relationships that Linda understood as valuable to research and leadership in higher education. In our later conversation with Harun Siljak (SF Co-host and EDGE Fellow), we learned that the role of Principle Investigator (PI) in academic research contexts can often be conflated with the role of Mentorship. We began to realise that these are better understood as distinctive roles that operate according to very different power and ethical relations. In a traditional PI/PostDoc or Supervisor/PhD relationship, the power relation is hierarchical by design. It can look a bit like a Master and Apprentice relationship, or sometimes it can look a bit like a Master and Servant relationship. As Harun described it, “A mentor is not a person who can fire you,” whereas a P.I. or Supervisor can be. In such situations, how can the 'mentee' ask difficult questions? How can conflicts of interest be resolved or even addressed in the first place? Similar to the Peer-Review session, we were once again teasing out urgent issues concerning research integrity and ethics in academic life through creative criticism.

Outside the Glucksman at UCC

Linda had organised an EDGE Leaders in Research lunchtime event to take place at University College Cork, so we took this opportunity to host our next Stranger Fictions session there as well. On an unusually warm day in June, EDGE fellows travelled from Dublin to meet with others based in and around UCC. The Leaders in Research series is targeted at PhD's, post-docs and academics. For each event, Linda interviews an academic and industry professional about their careers, their pathways, some challenges they faced, their successes and fails, and draws out take away points of advice they could offer to current researchers. These are insightful occasions for researchers to hear about the journeys of others working between academia and industry. Following tea, sandwiches and conversation, (and a short but rather roasting walk across campus, there really was a heat-wave, honest!), the Stranger Fictions group convened in a sunny corner of Bobo cafe. On the day, we were a mix of people from EDGE, CONNECT, UCC and CIT.

In our preparatory chats, Linda had decided that the best way she could seed and catalyse this Stranger Fictions session was for her to act as a mentor to the group, to sit and open up a channel, listen and wait for some response.

This was a risky and courageous move, and it really worked. Following a ritualised reading of dictionary and etymology descriptions of the word mentor and mentorship by myself and Harun, Linda opened with a question:

So, what would you like to talk about today, since the last time we met?

We can talk about anything you want.

Take your time.

No pressure.

Linda Ryan

I don't think any of us were expecting what followed. After a burst of nervous laughter and 30 seconds of silence softened by the sounds of the café, a voice broke in asking:

DNM: Could we talk about what research is for?

LR: Yeah. Sure. Do you want to start?

DNM: Em. Yeah. I guess, when I say 'what is research for?' I suppose what I mean is at what point does it meet the non-research world. You know? What's the point of contact between research and non-research?

Thus, artist Dennis McNulty embraced the space of deliberation and thinking-out-loud, priming the air for our conversation. You'll have to listen to get a good sense of this session, transcribing doesn't cut it (and even the audio leaves out all sorts of body language). But to tempt you, let me just say that Linda responded to Dennis' question with another question: What does that mean for you? And this opened up a conversation around the drive towards 'optimisation' in research, even against larger realities of scarce resources, sustainability and mortality. What unfolded was a fascinating, emotionally intelligent and deeply honest conversation that surprised and touched us all, and led us to both appreciate and challenge our understanding of the ongoing role of mentorship (and human relationships) in our lives, whether we act as mentors or mentees. And we certainly spelled a few things out in our writings.

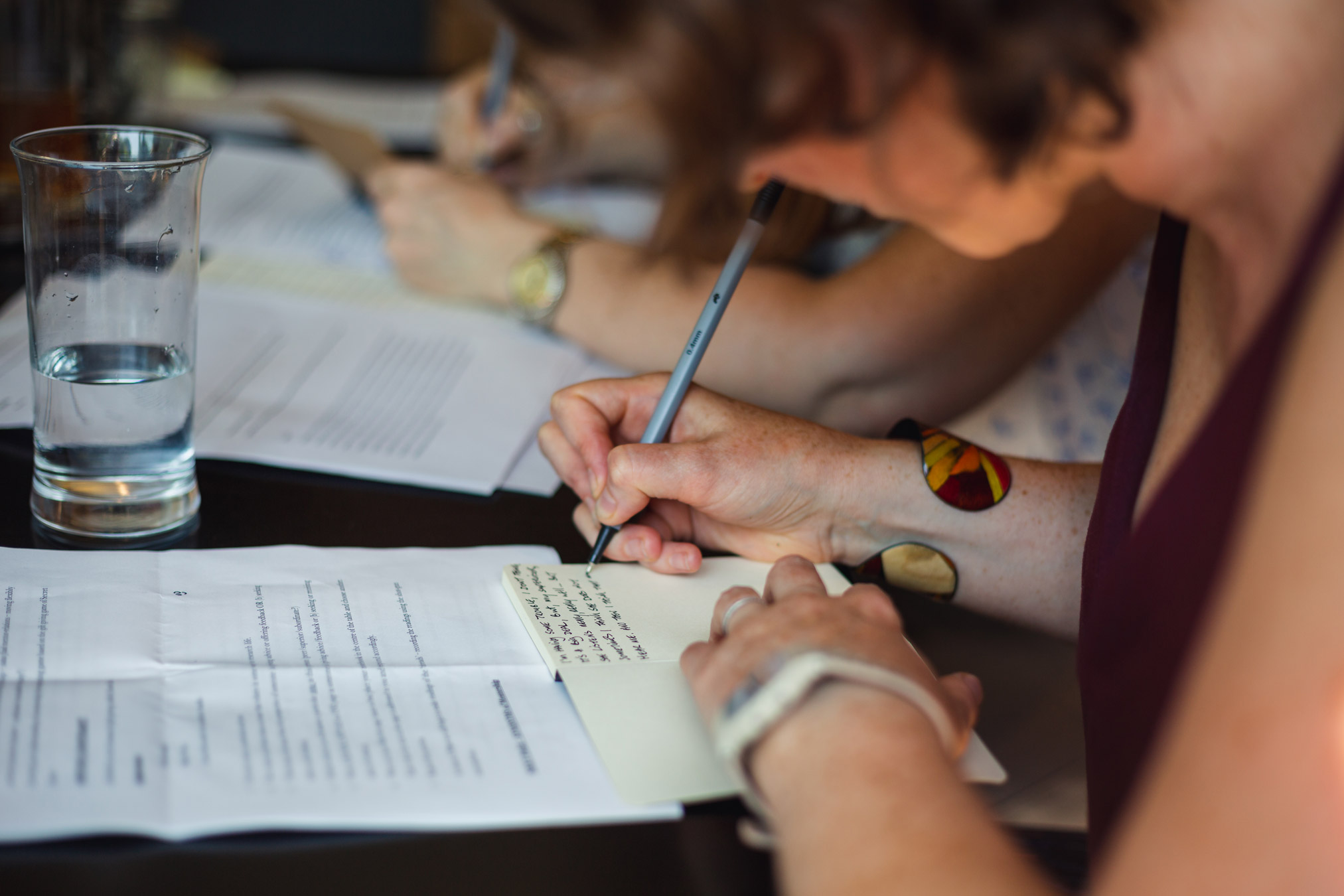

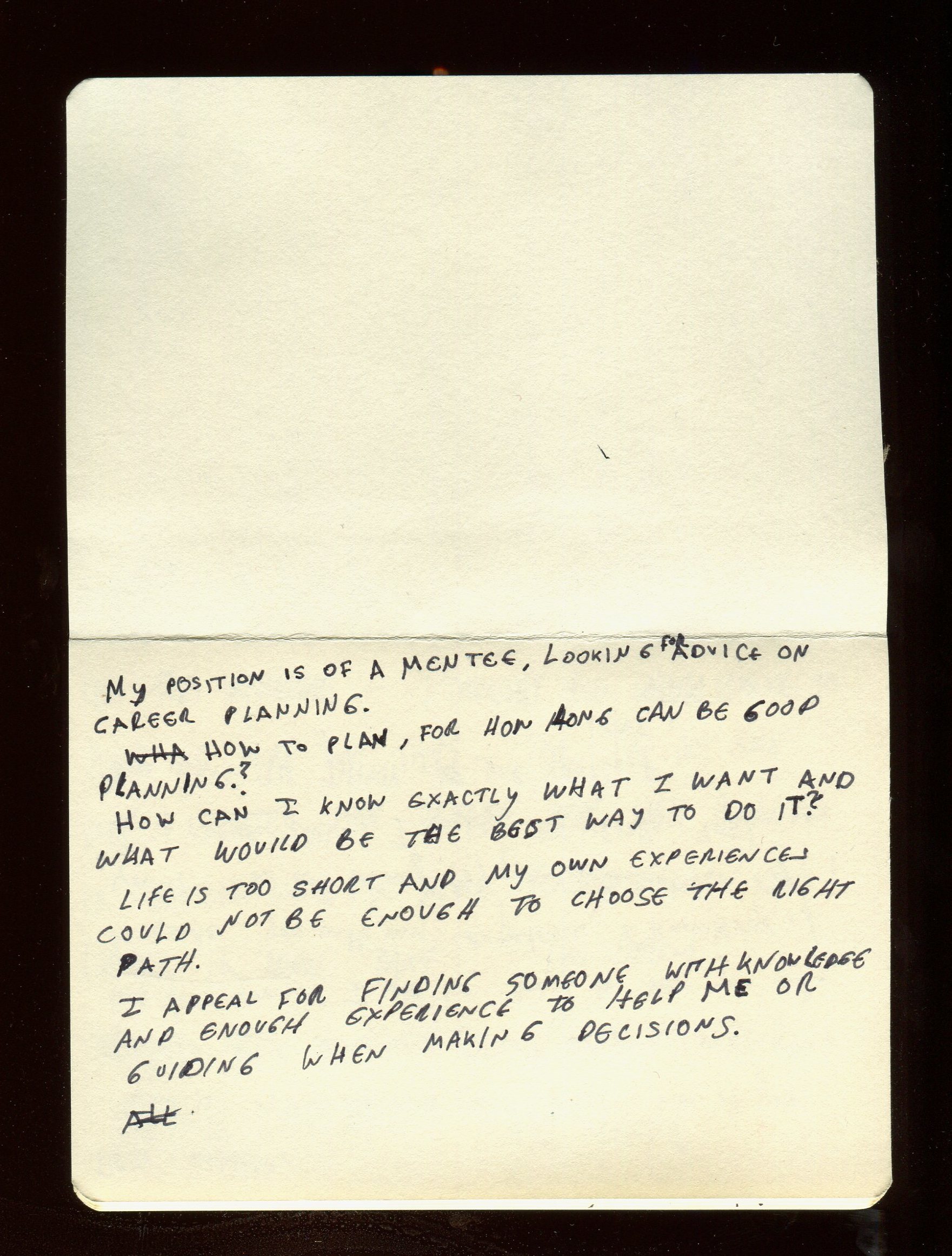

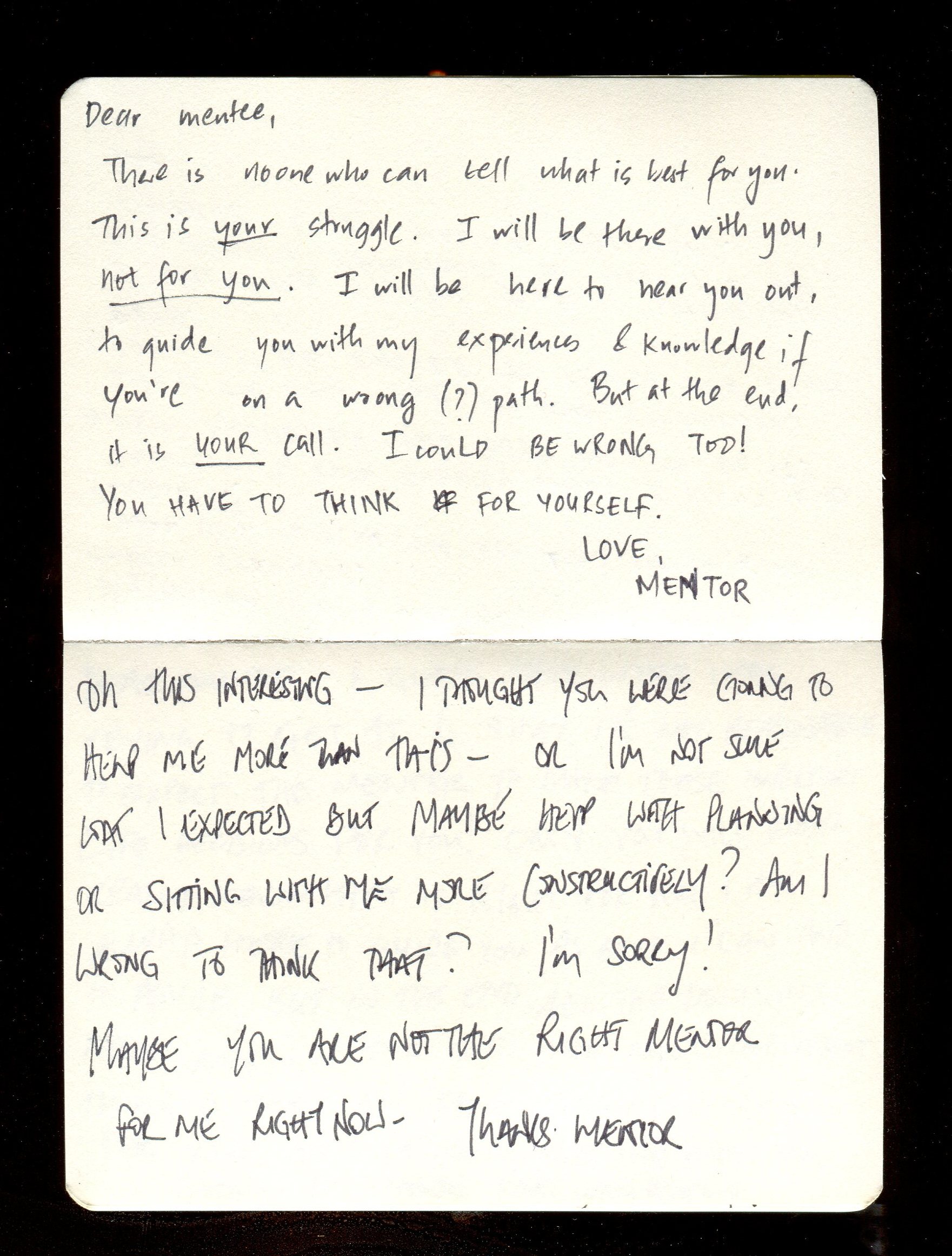

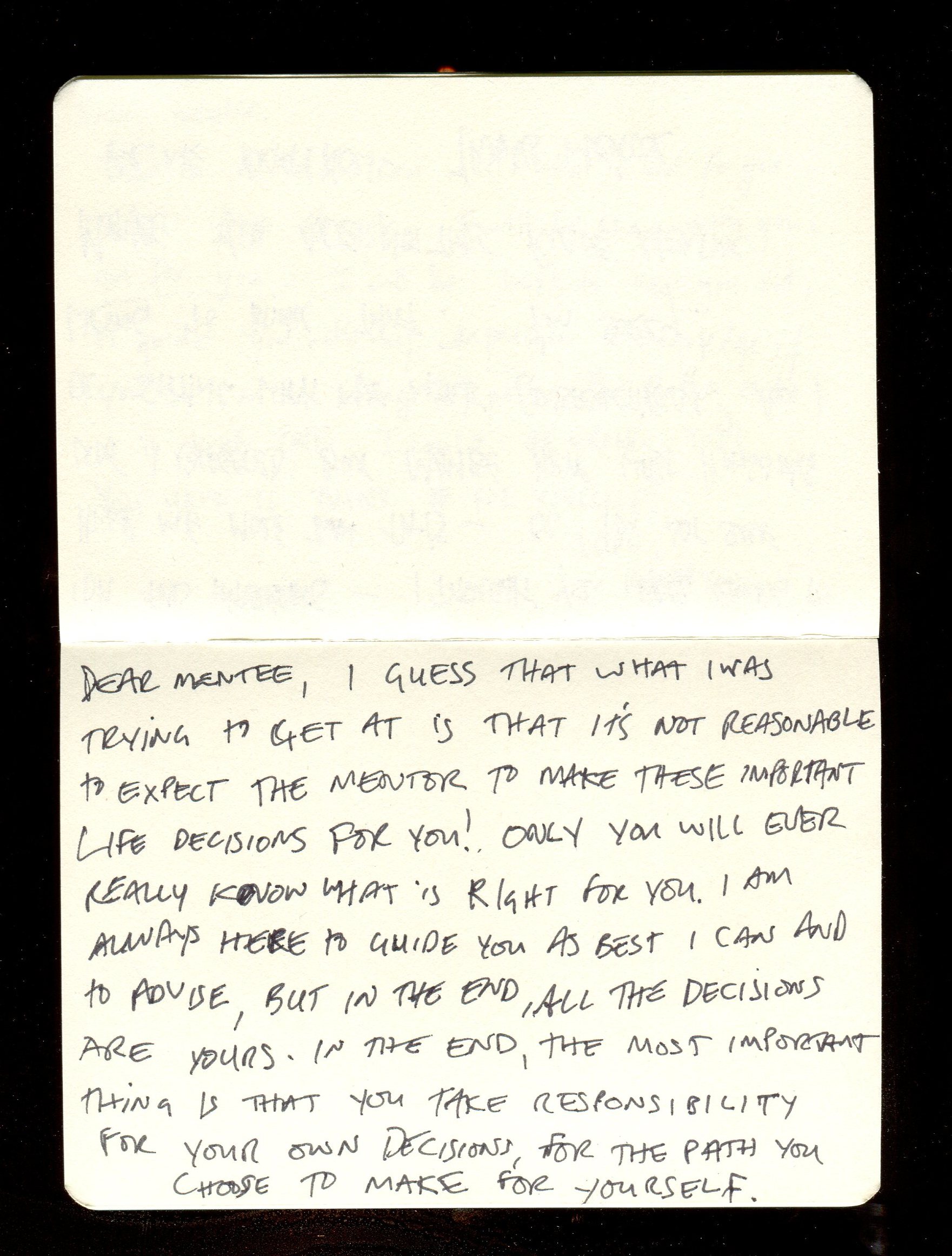

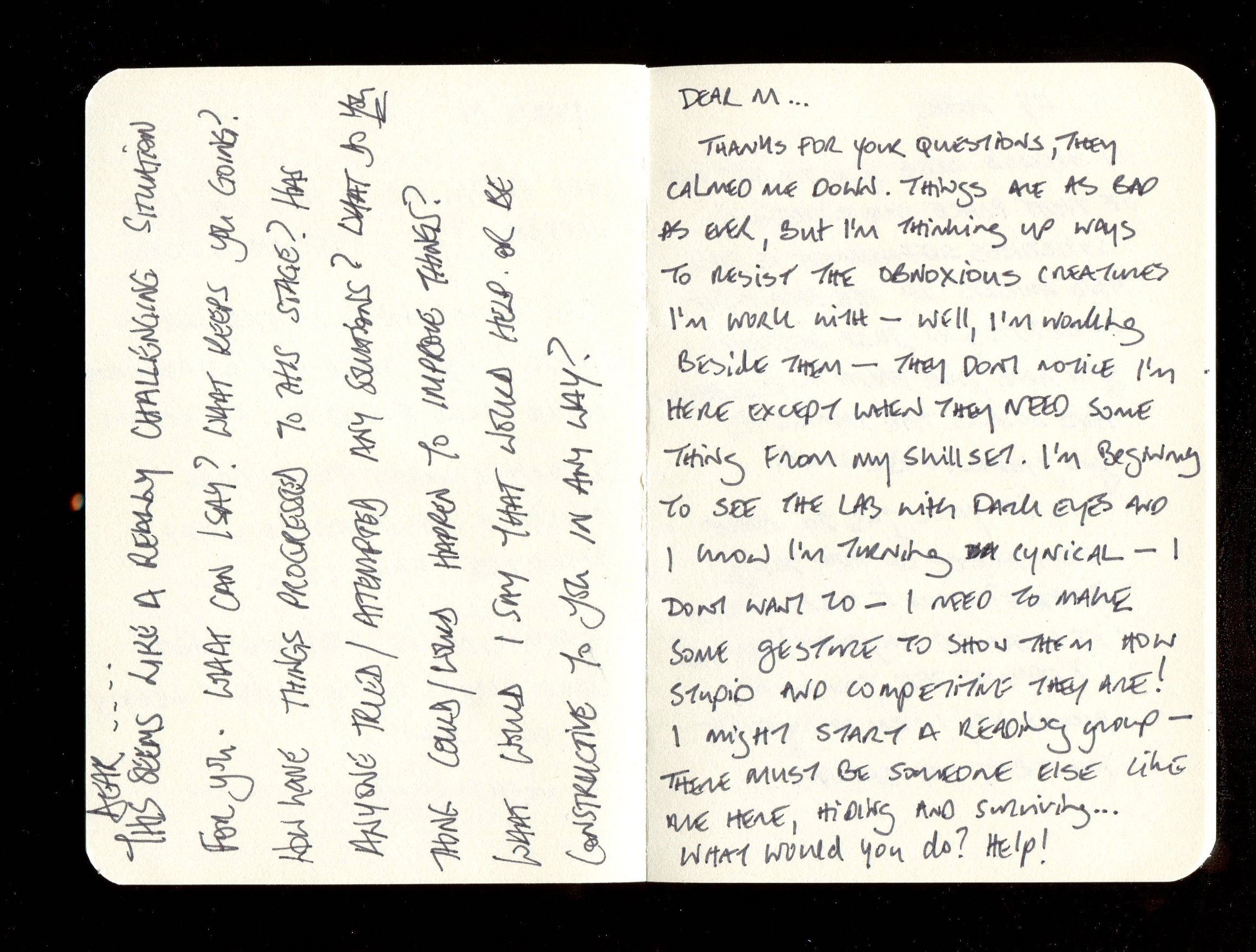

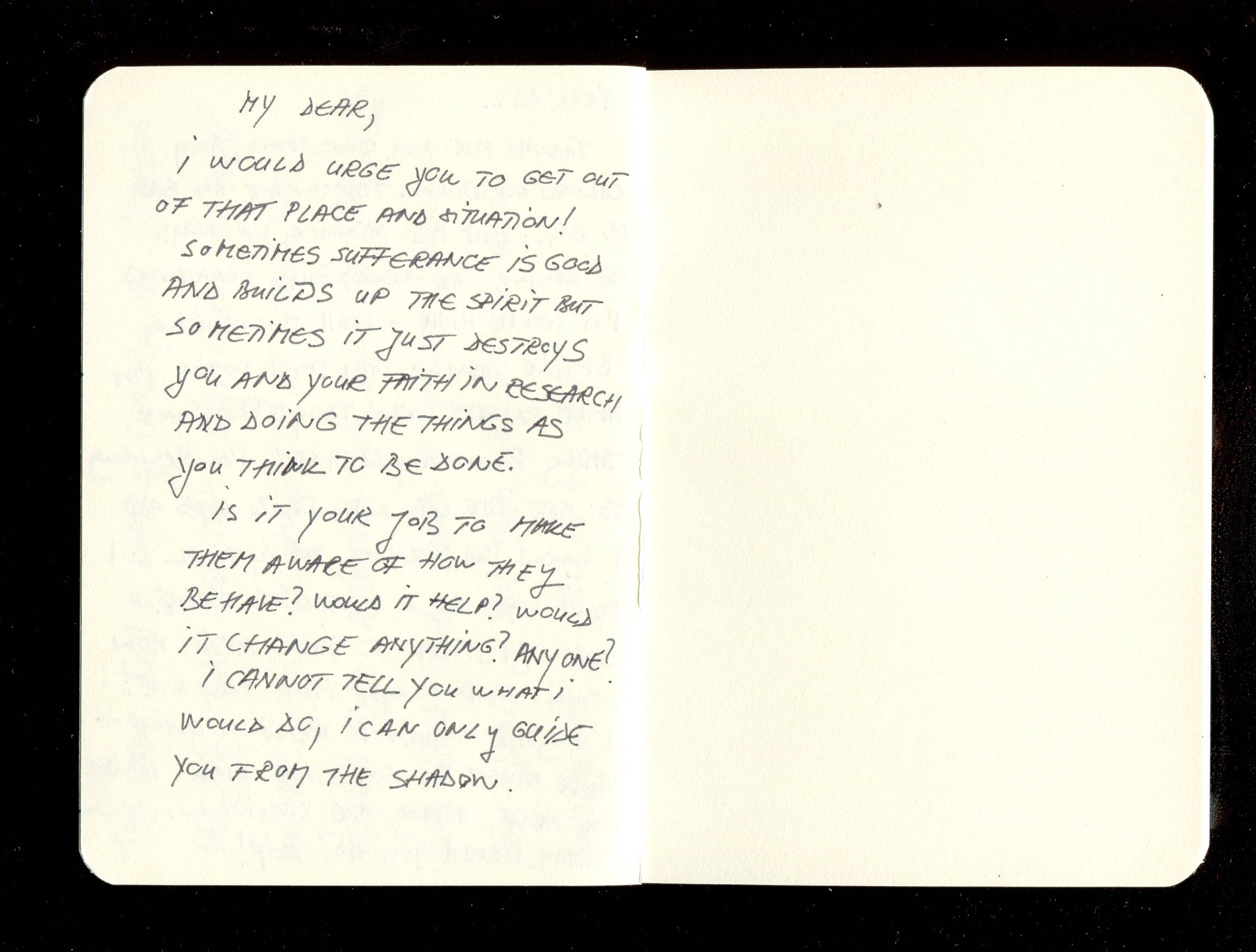

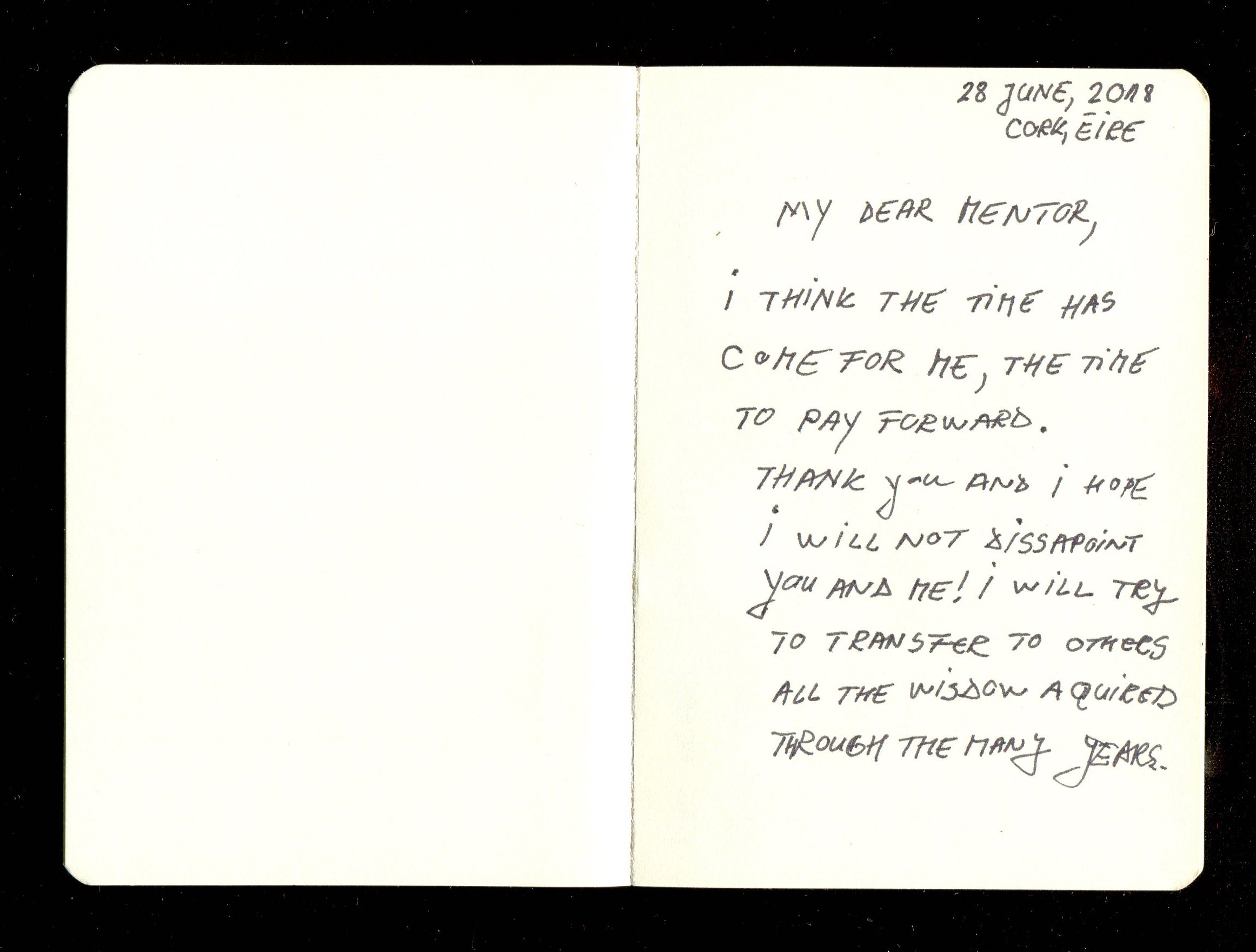

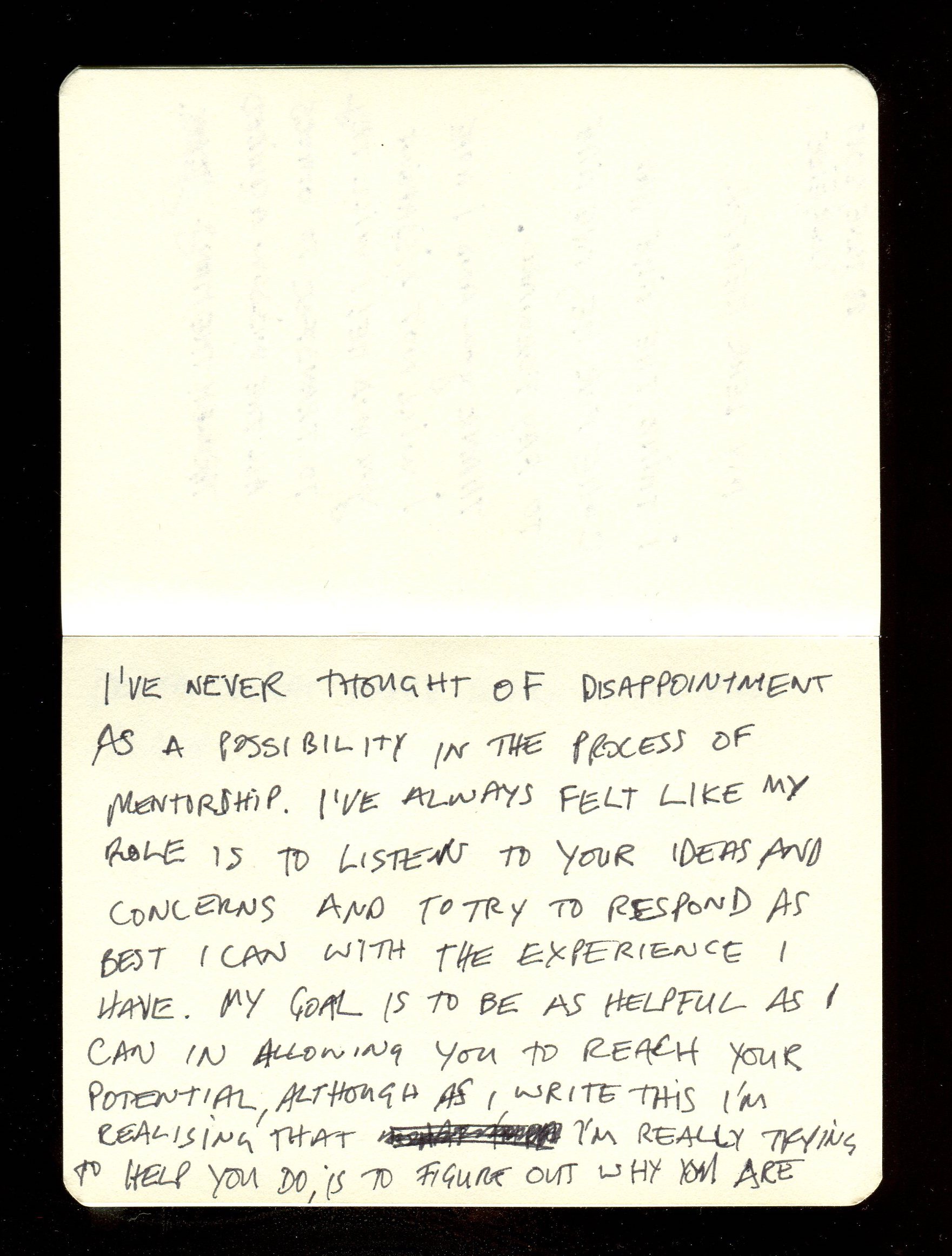

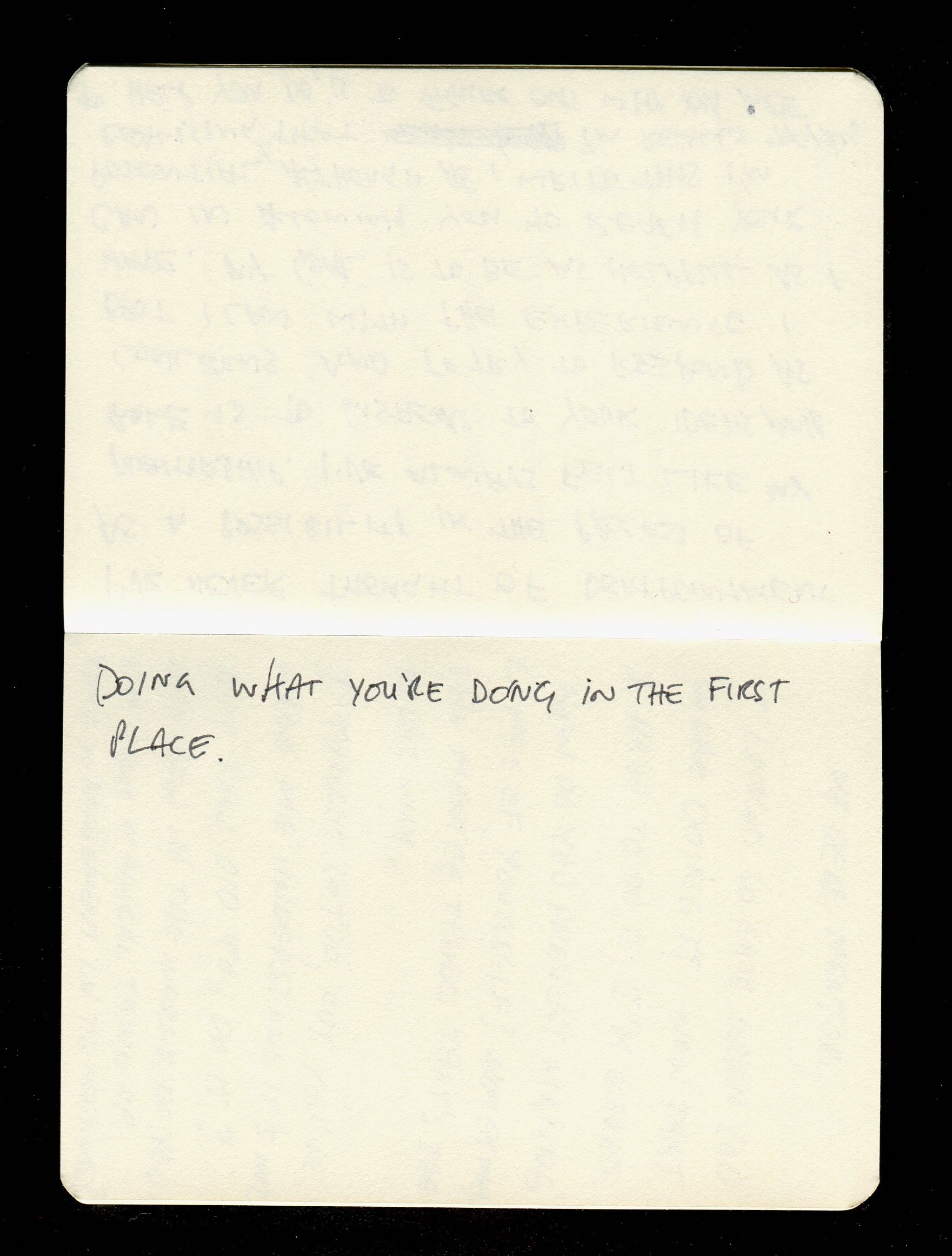

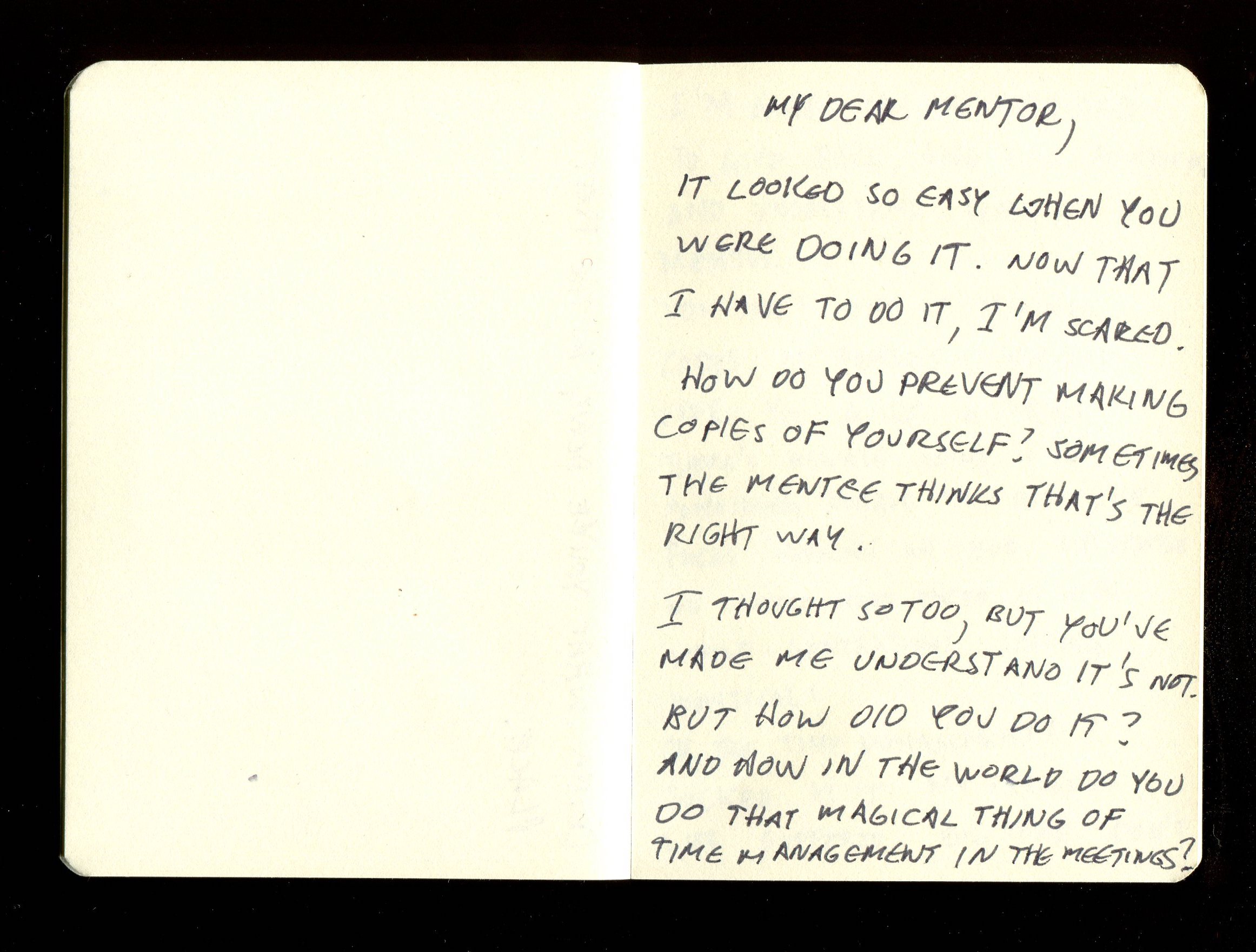

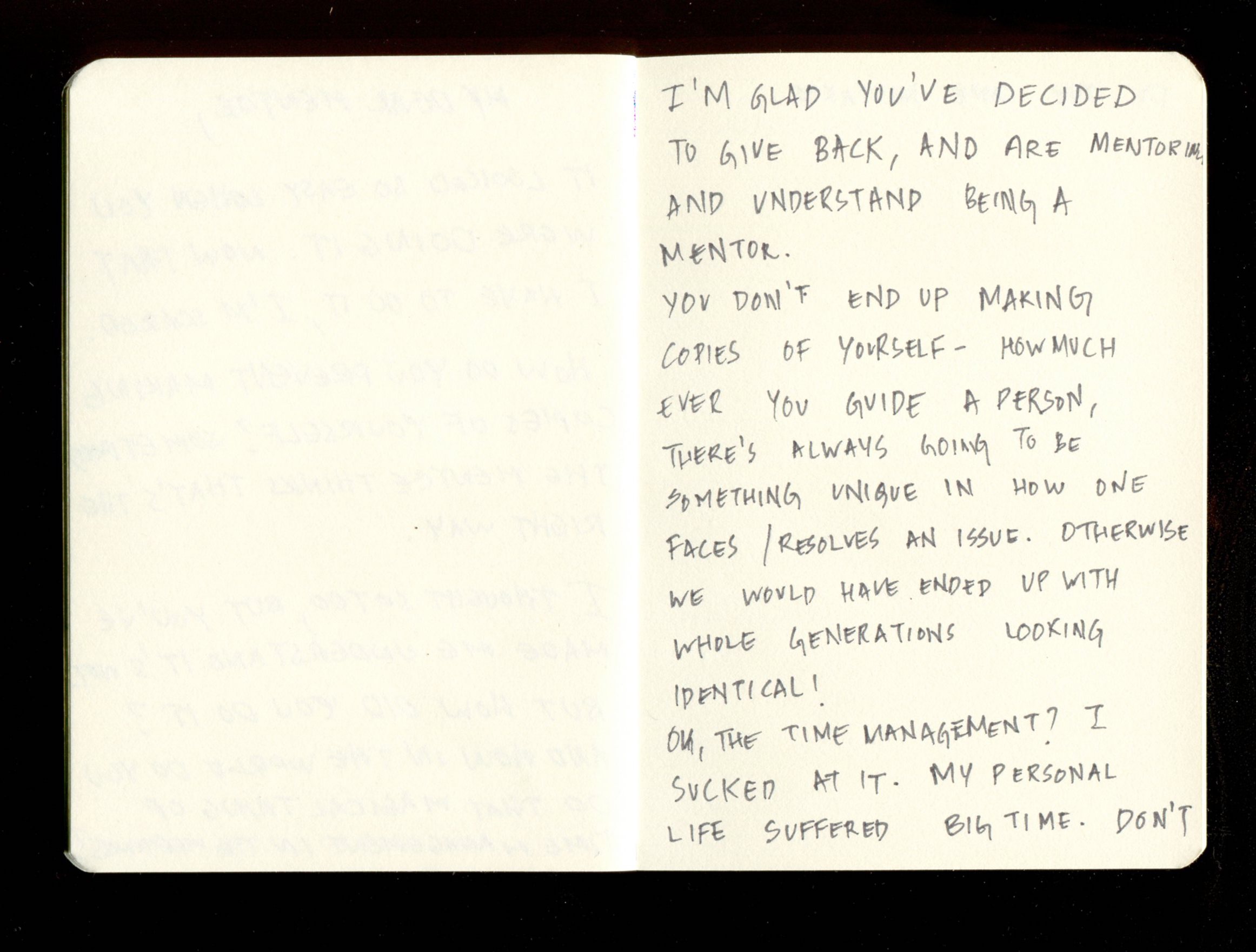

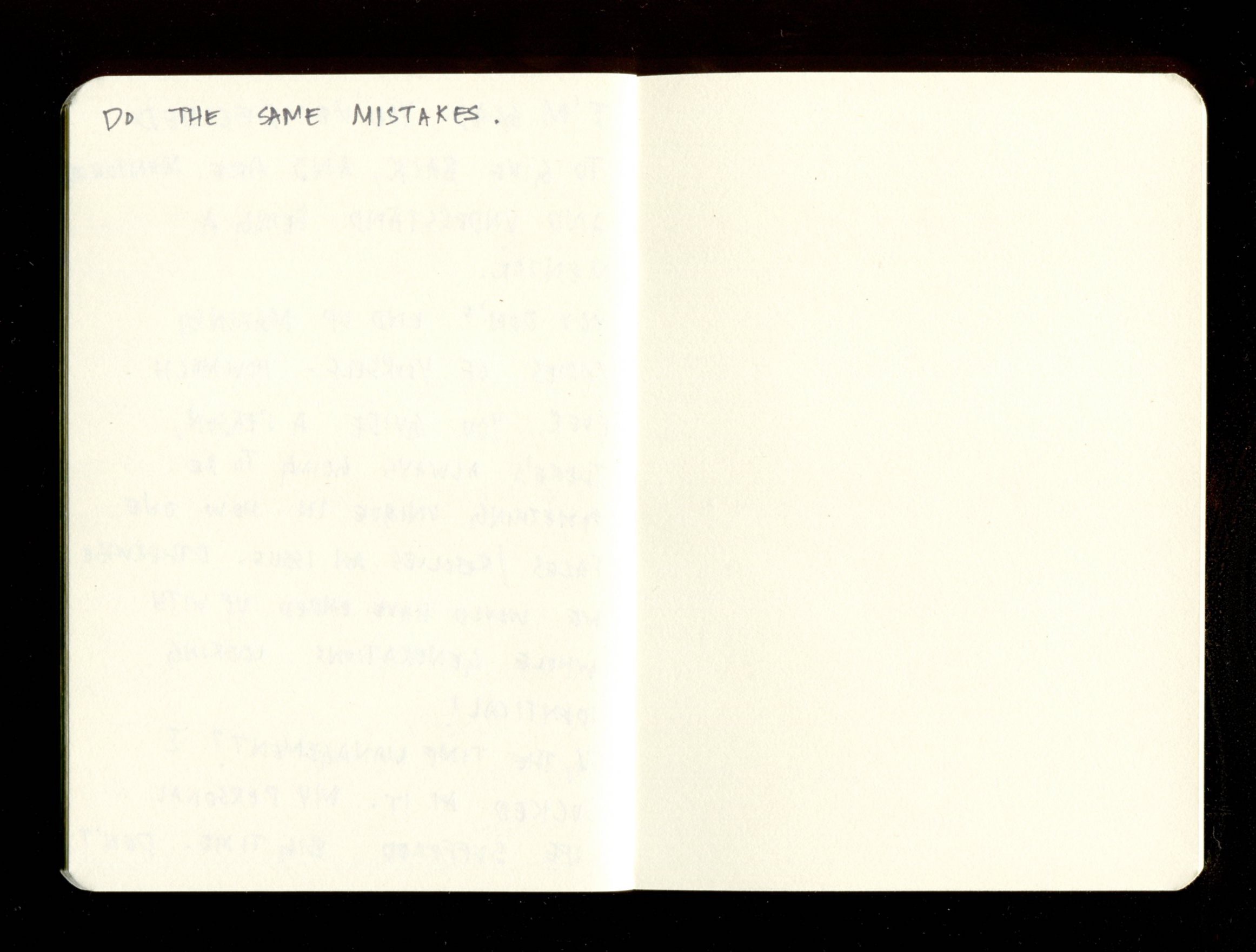

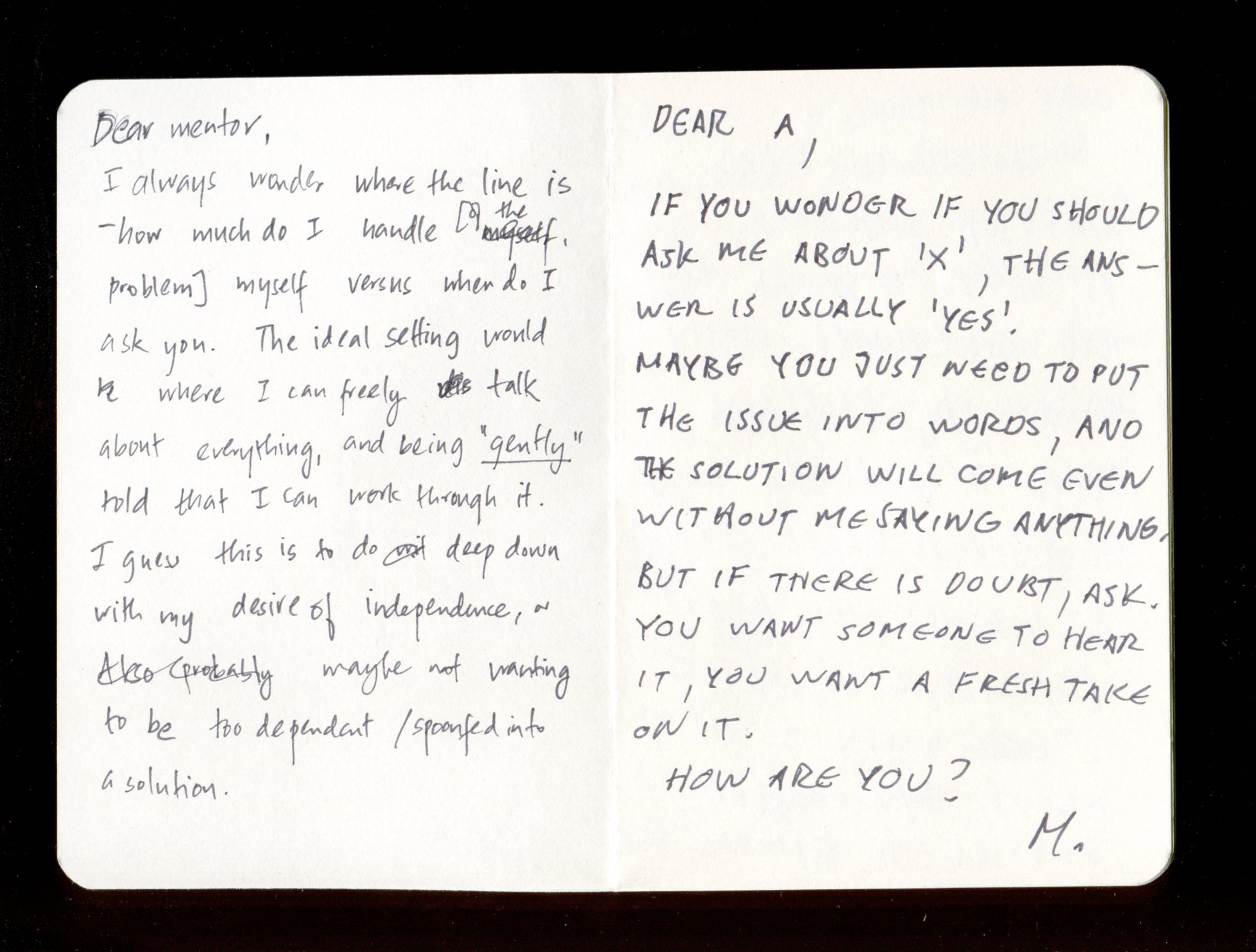

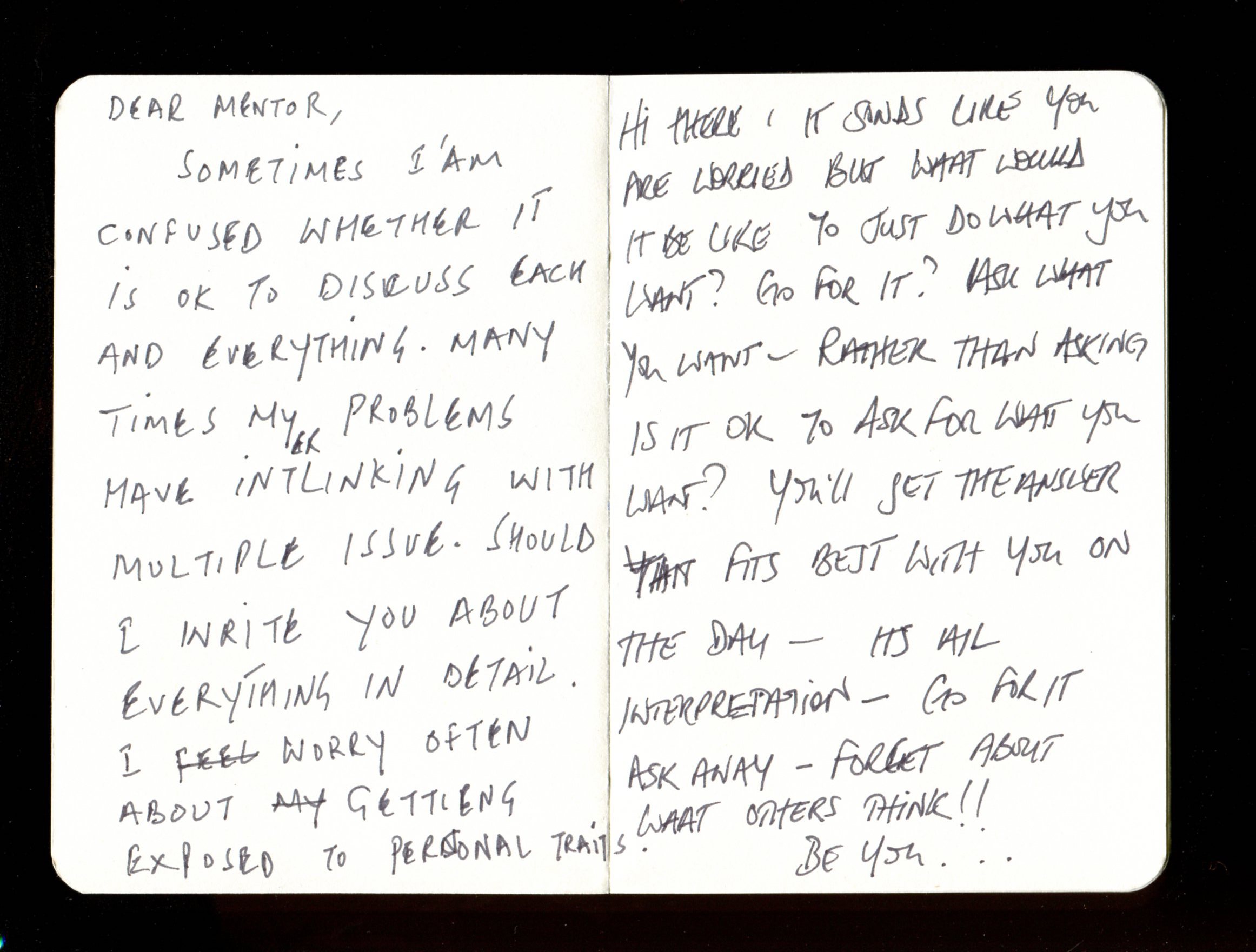

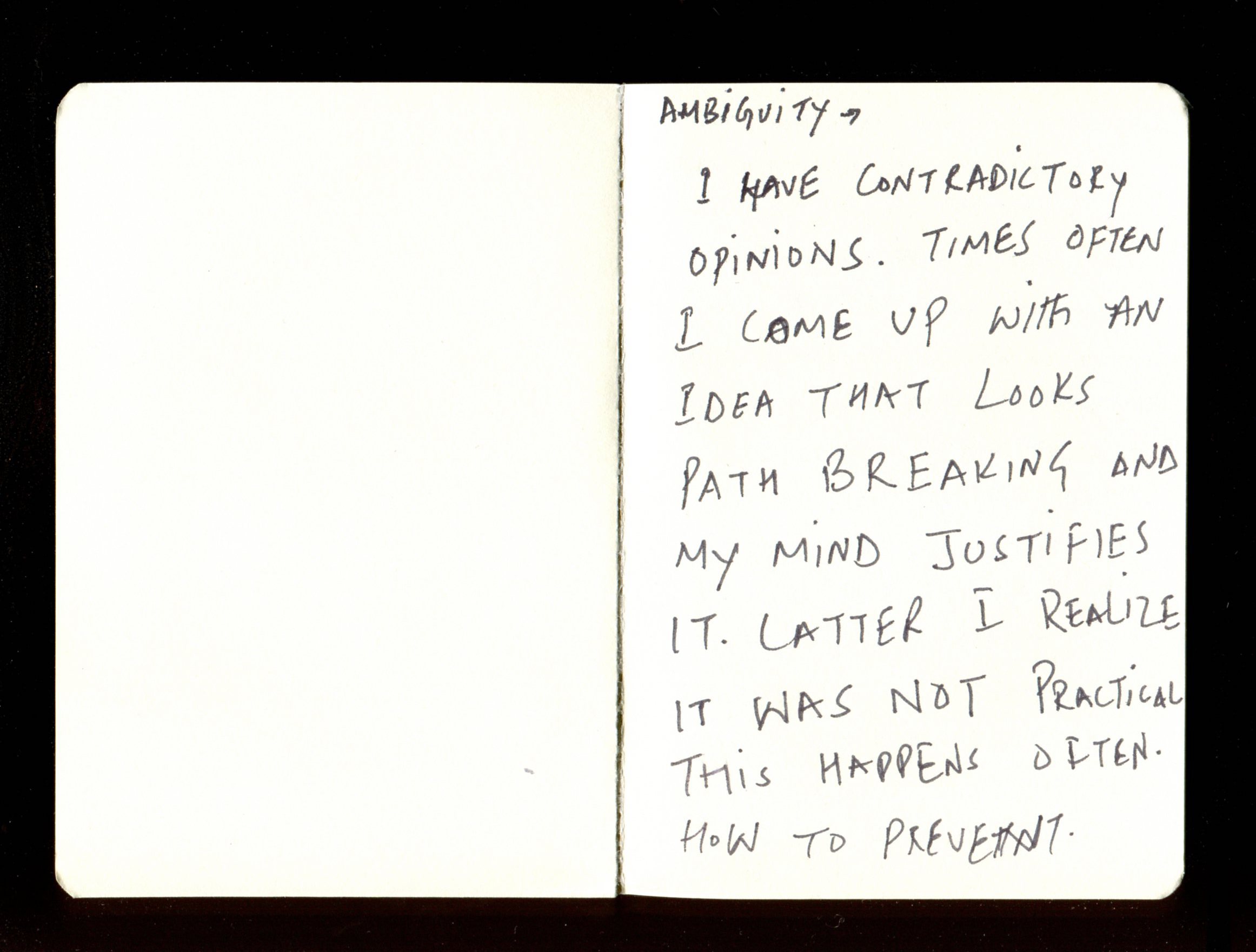

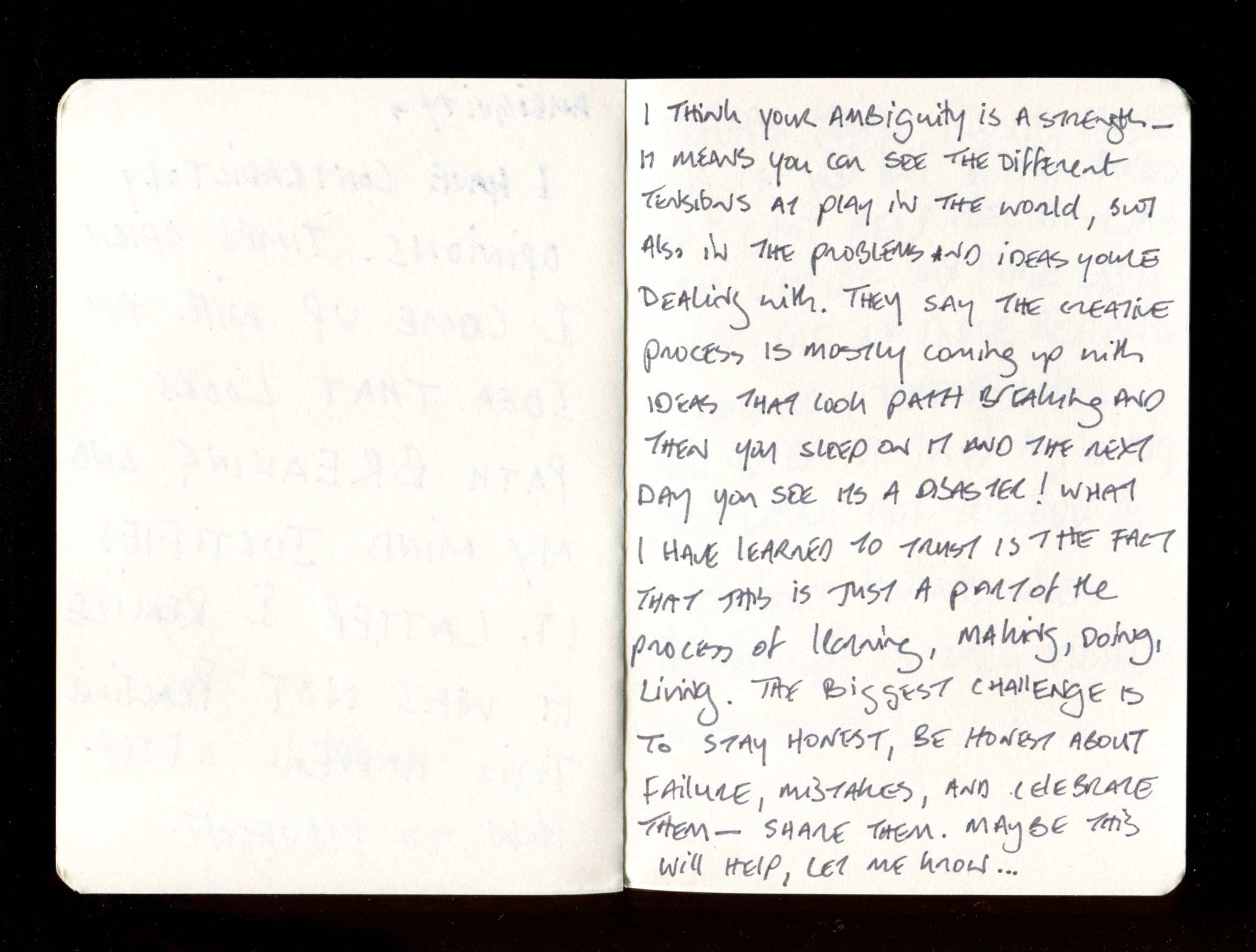

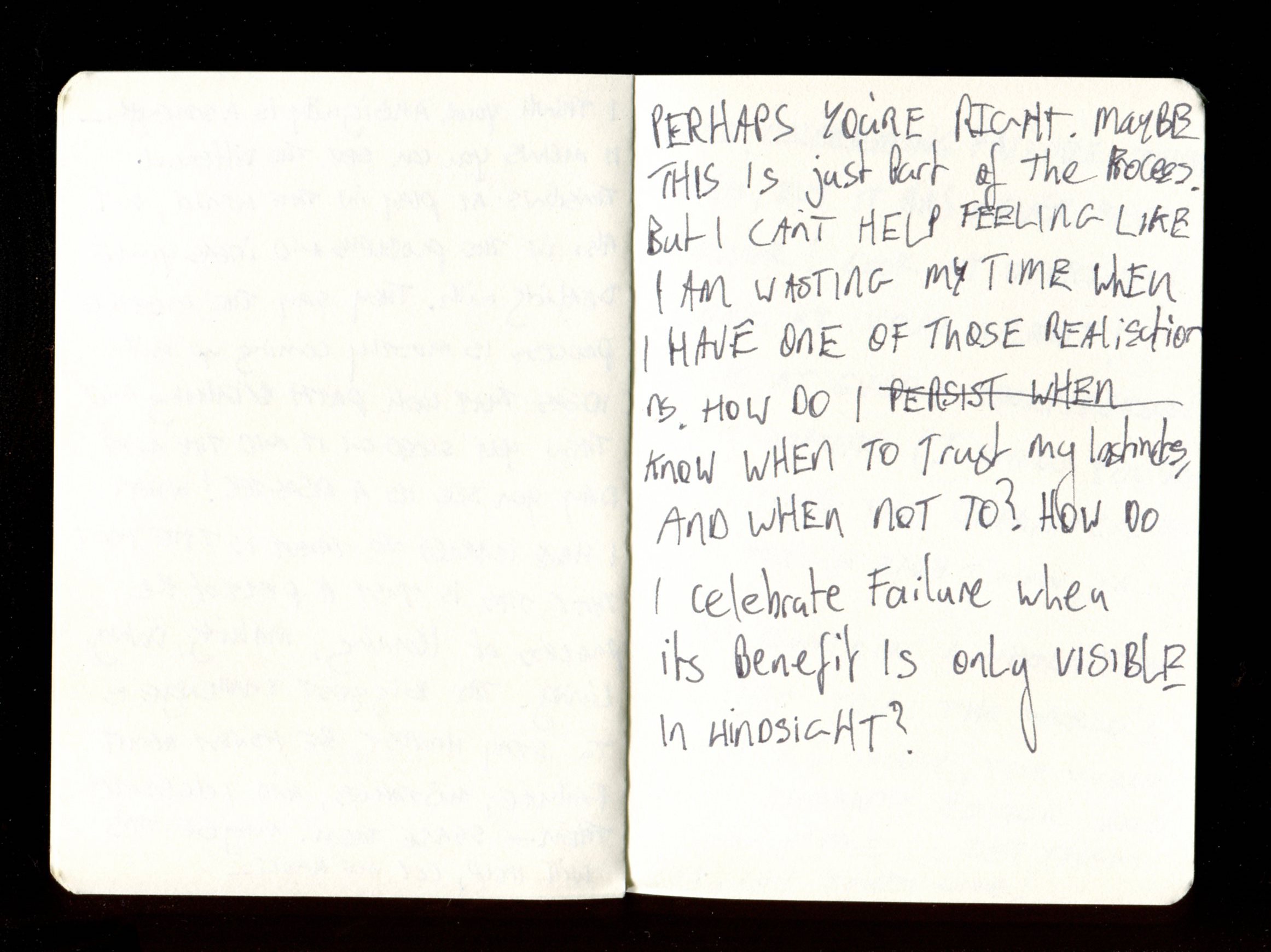

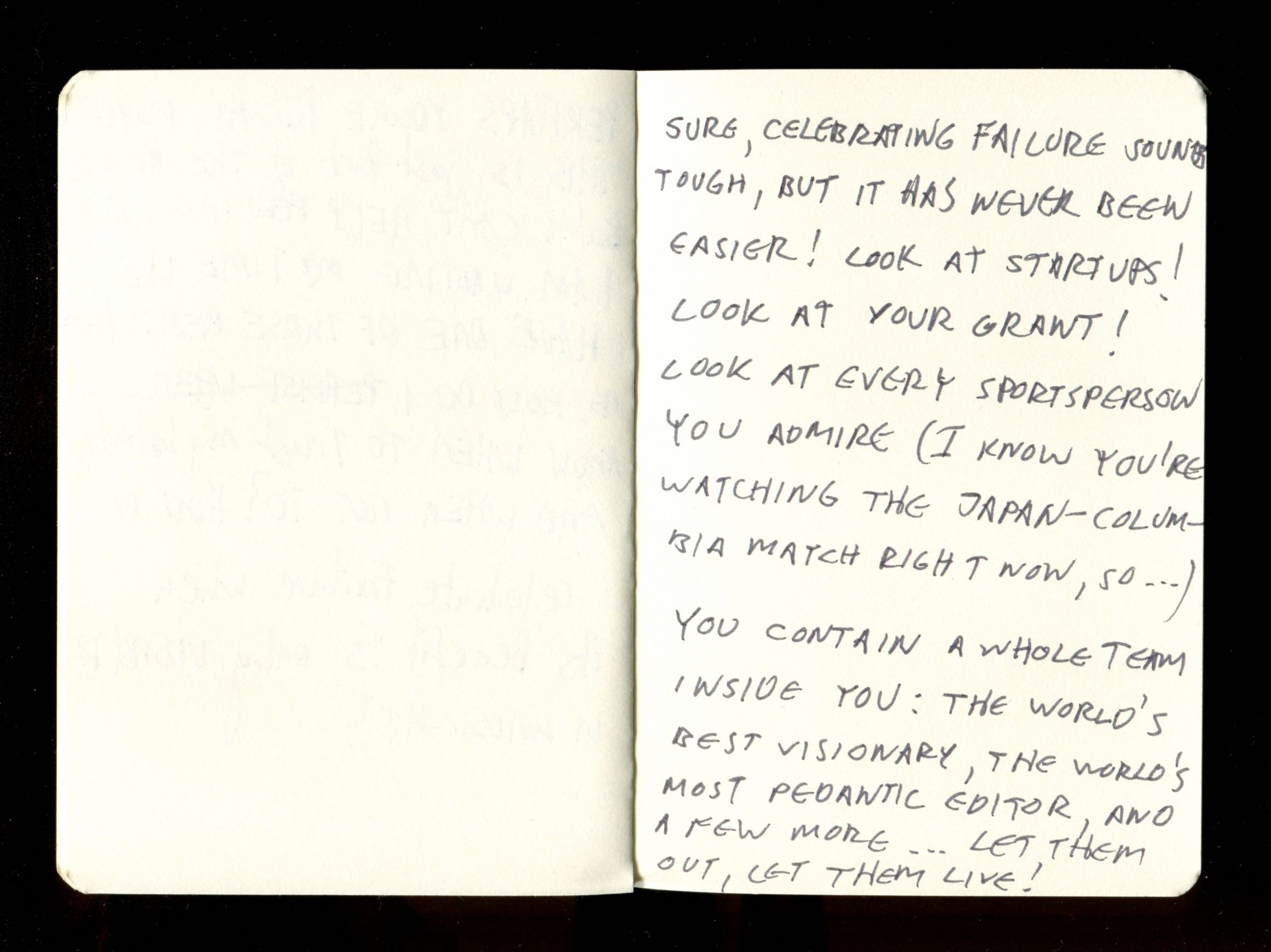

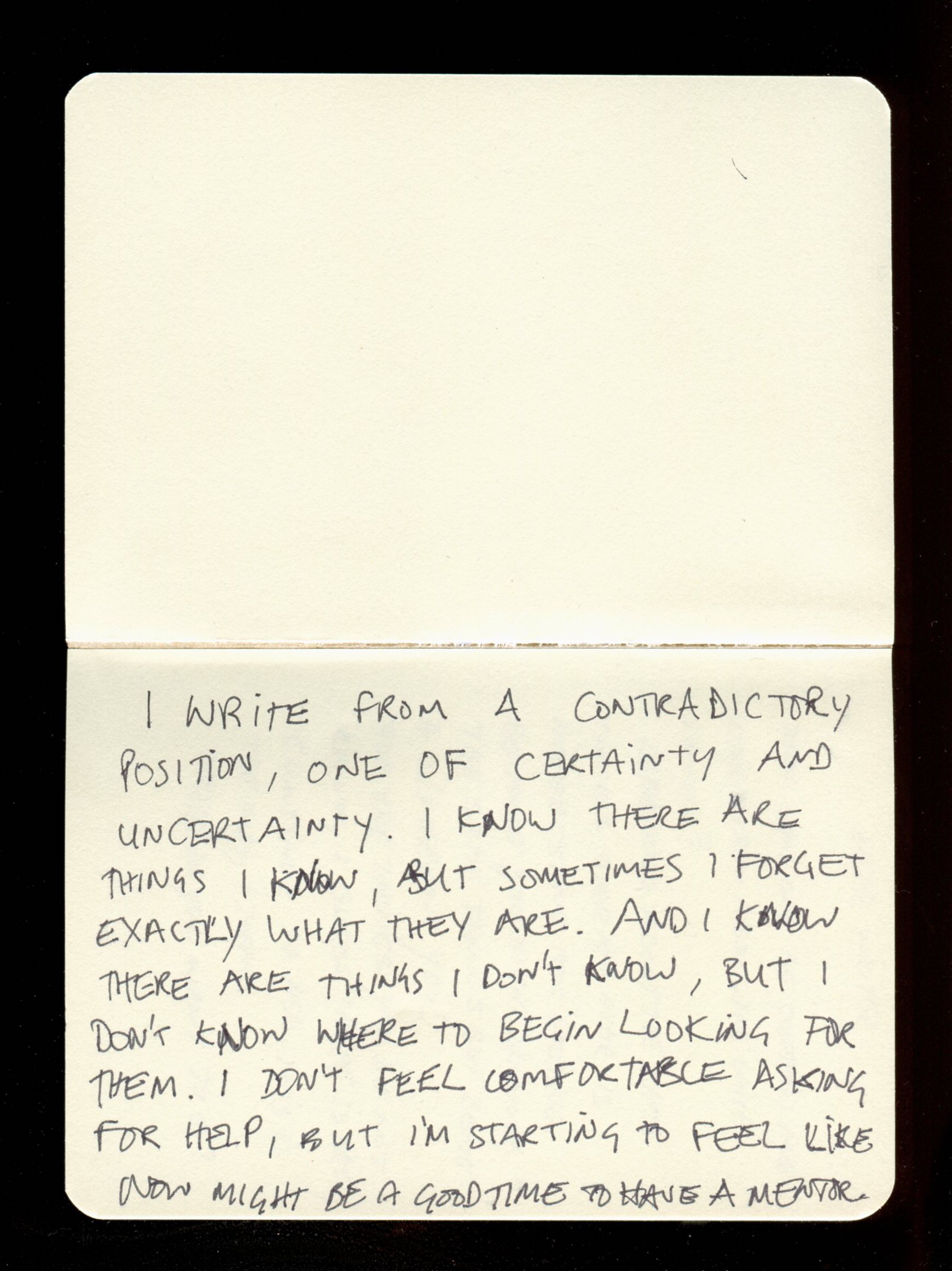

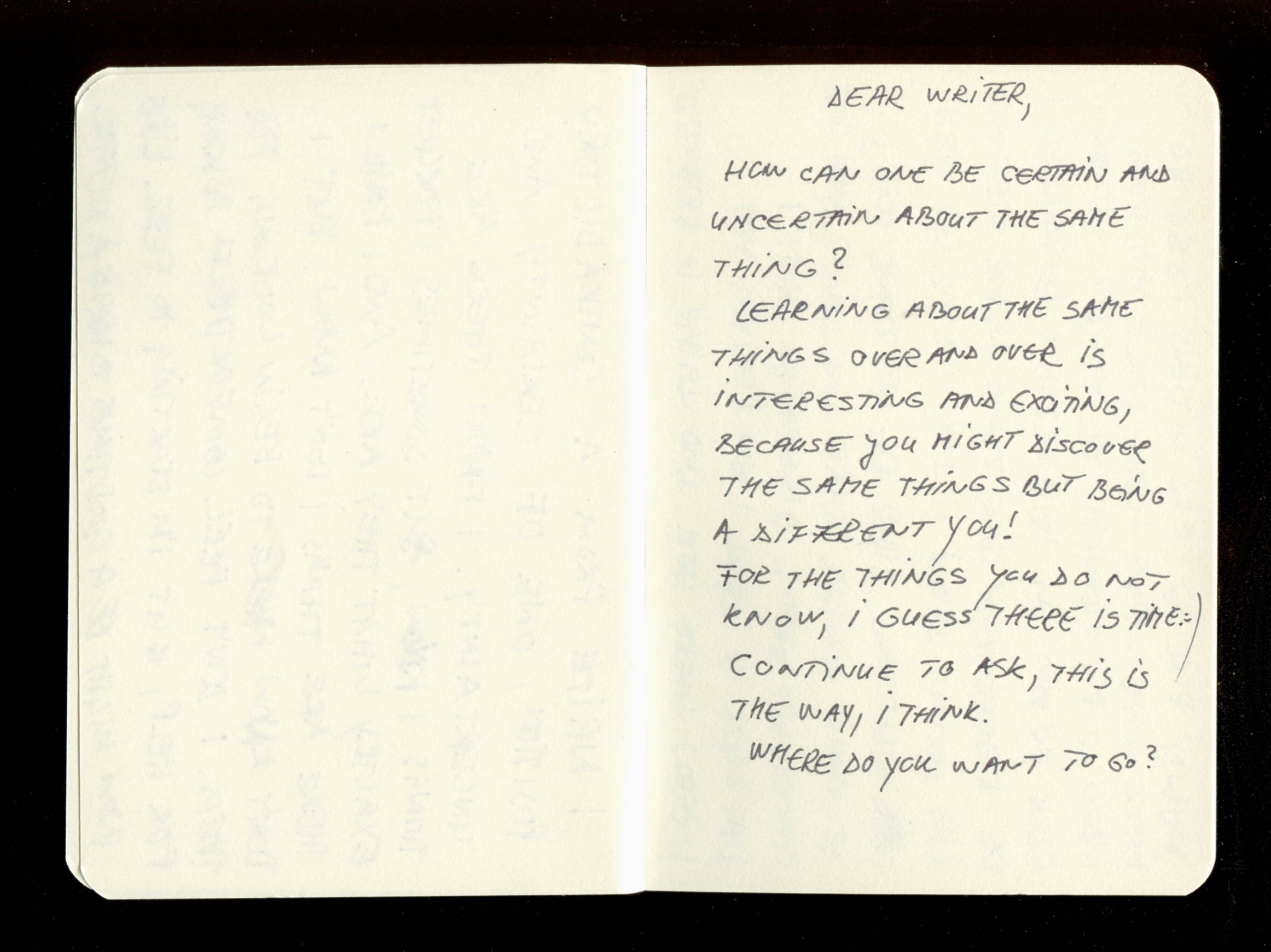

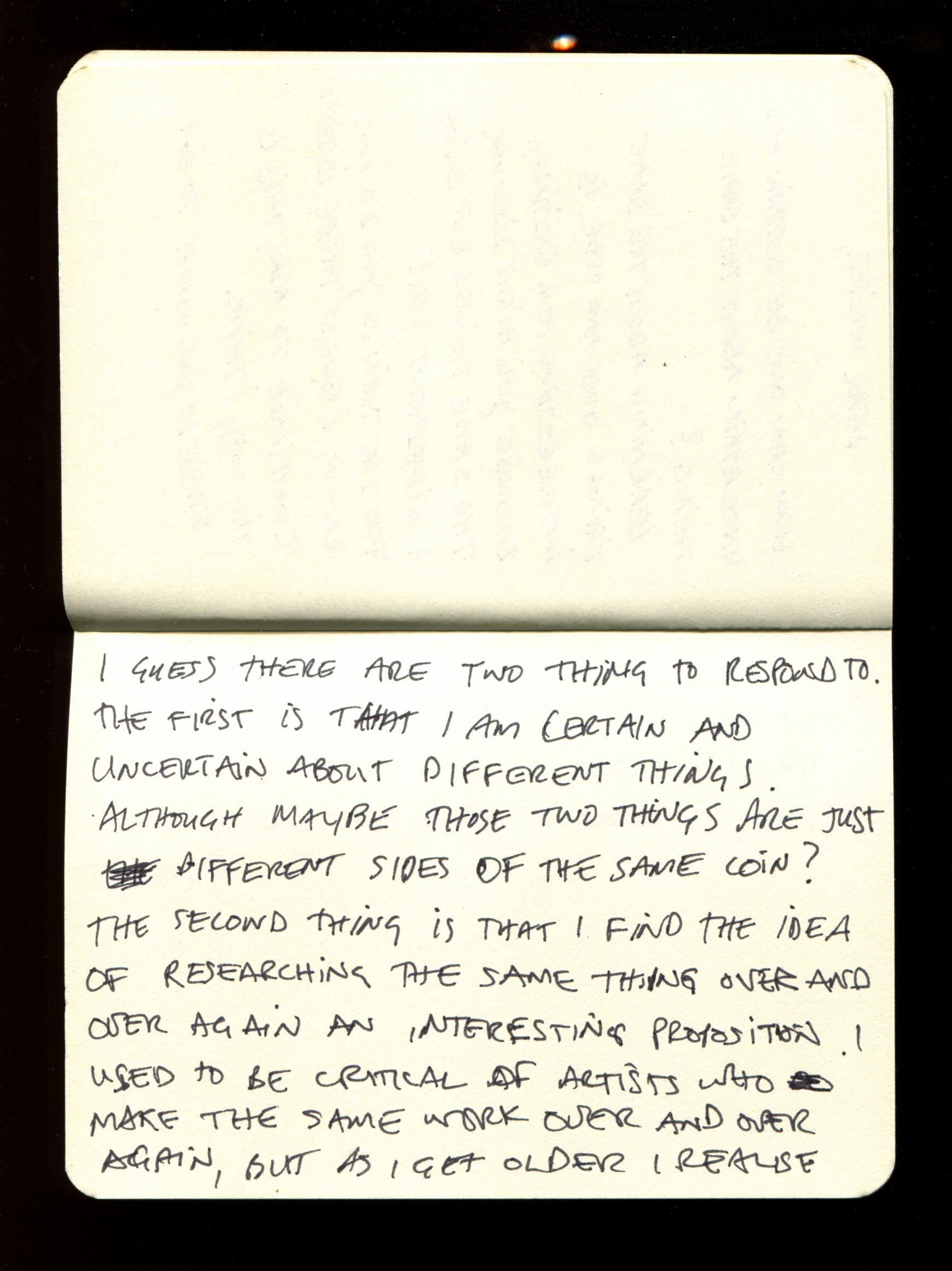

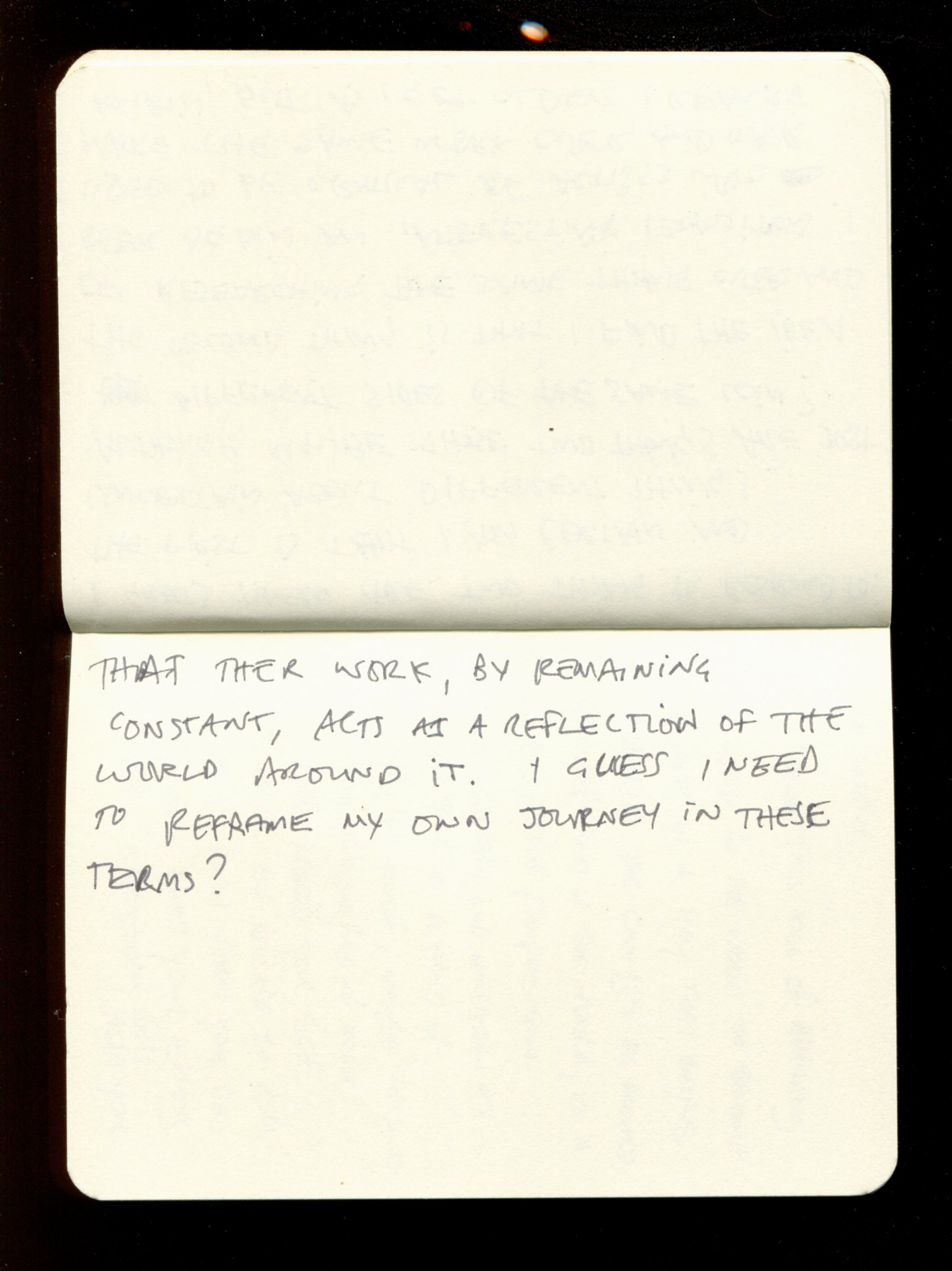

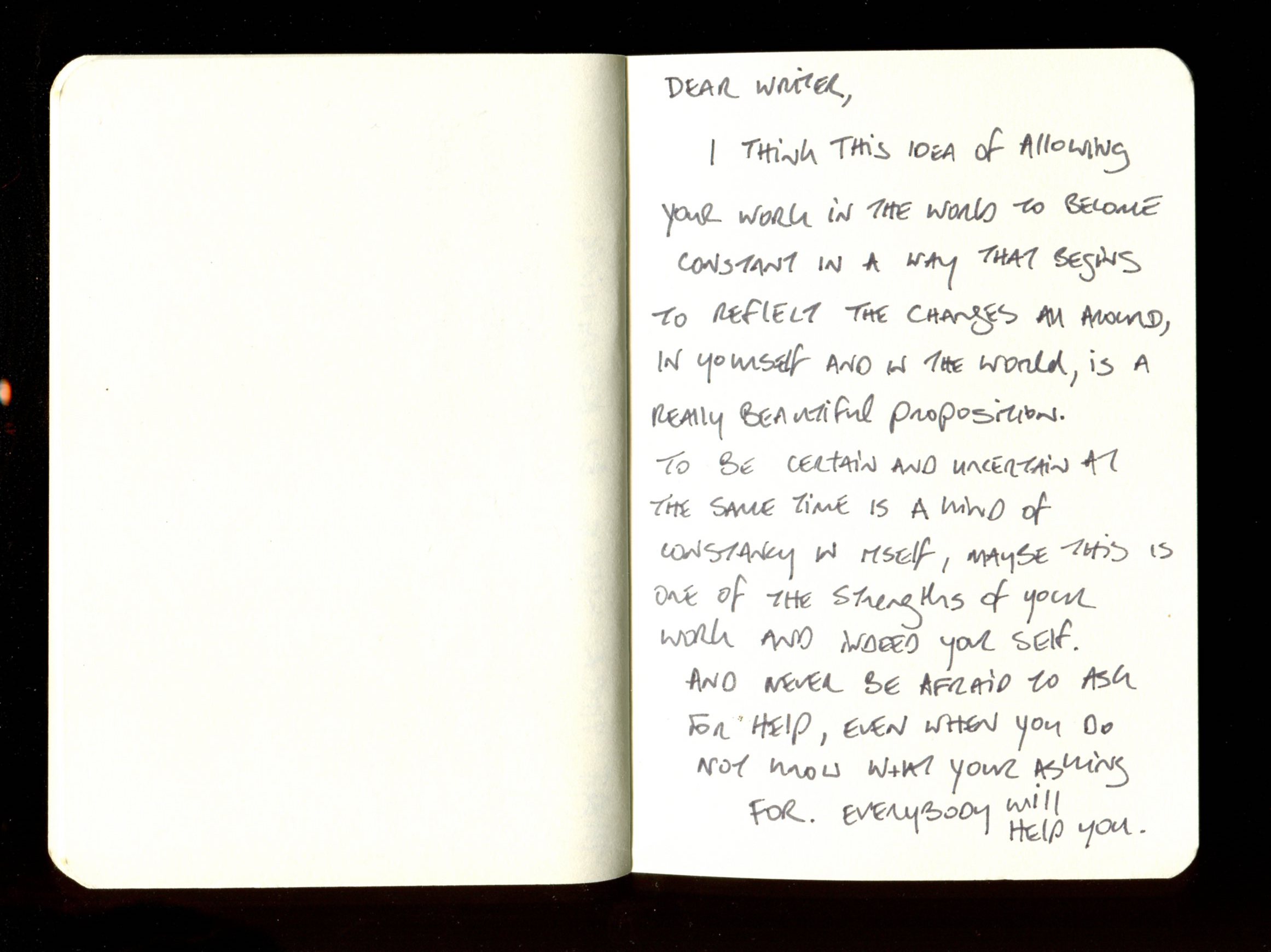

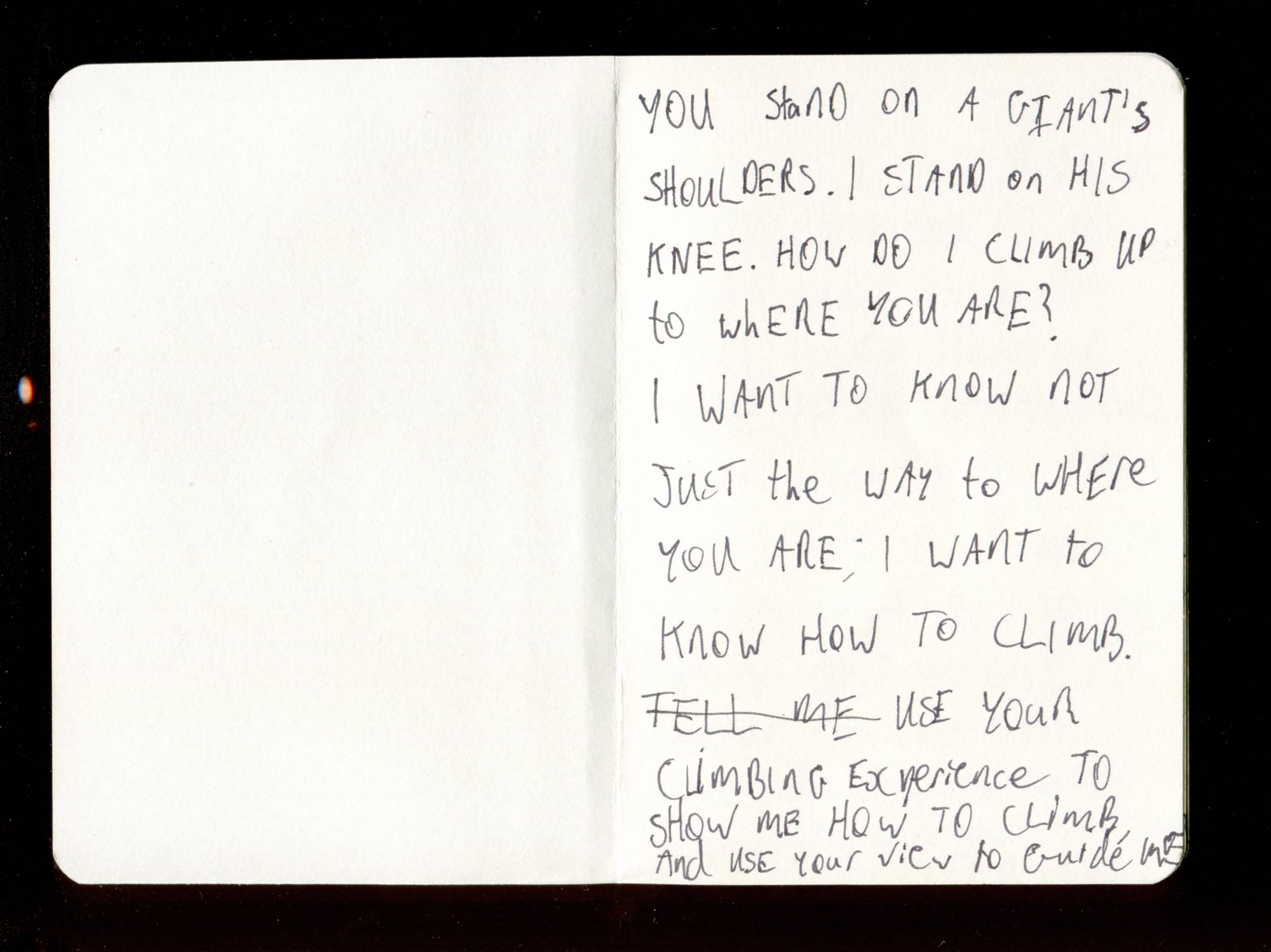

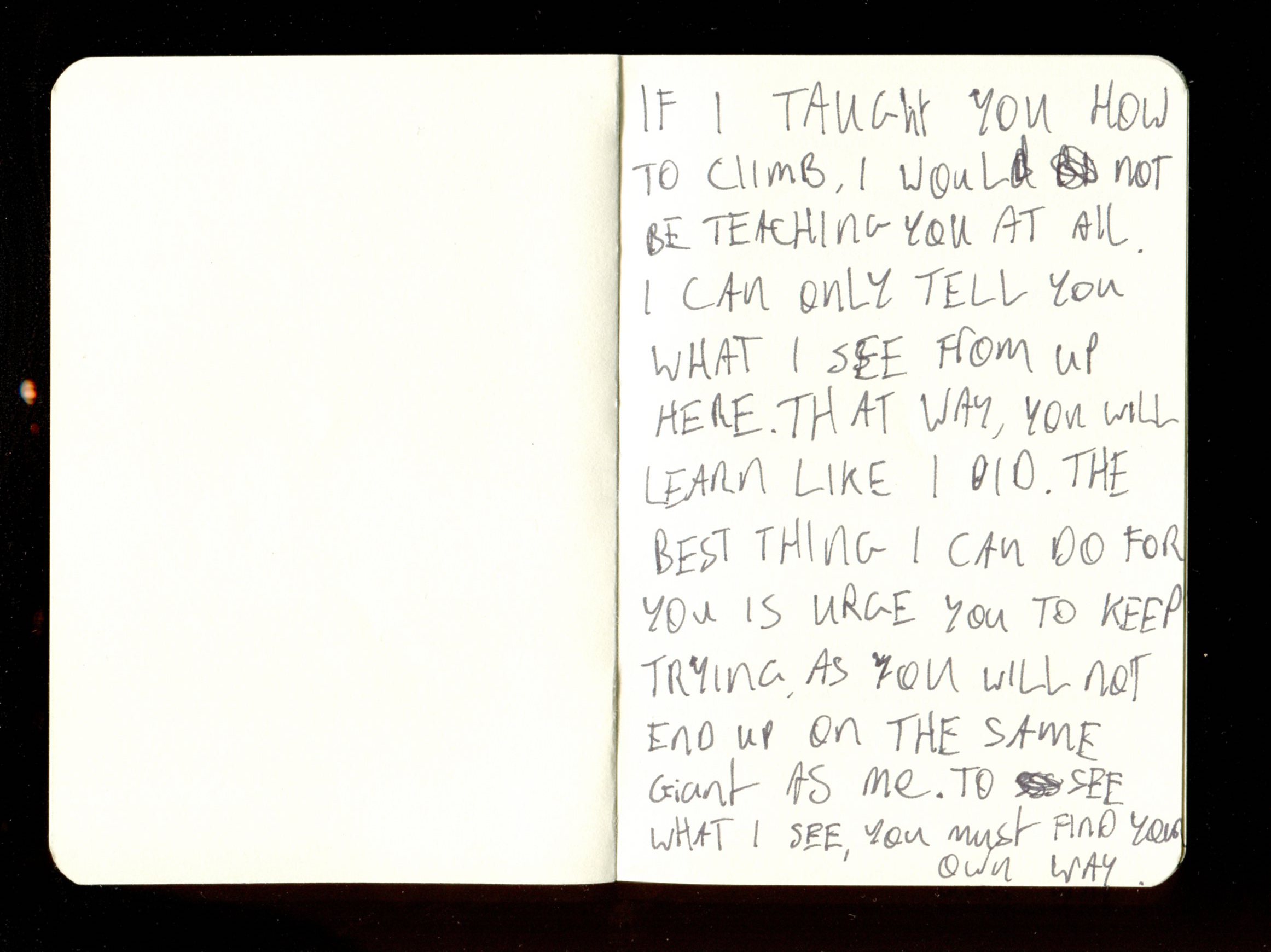

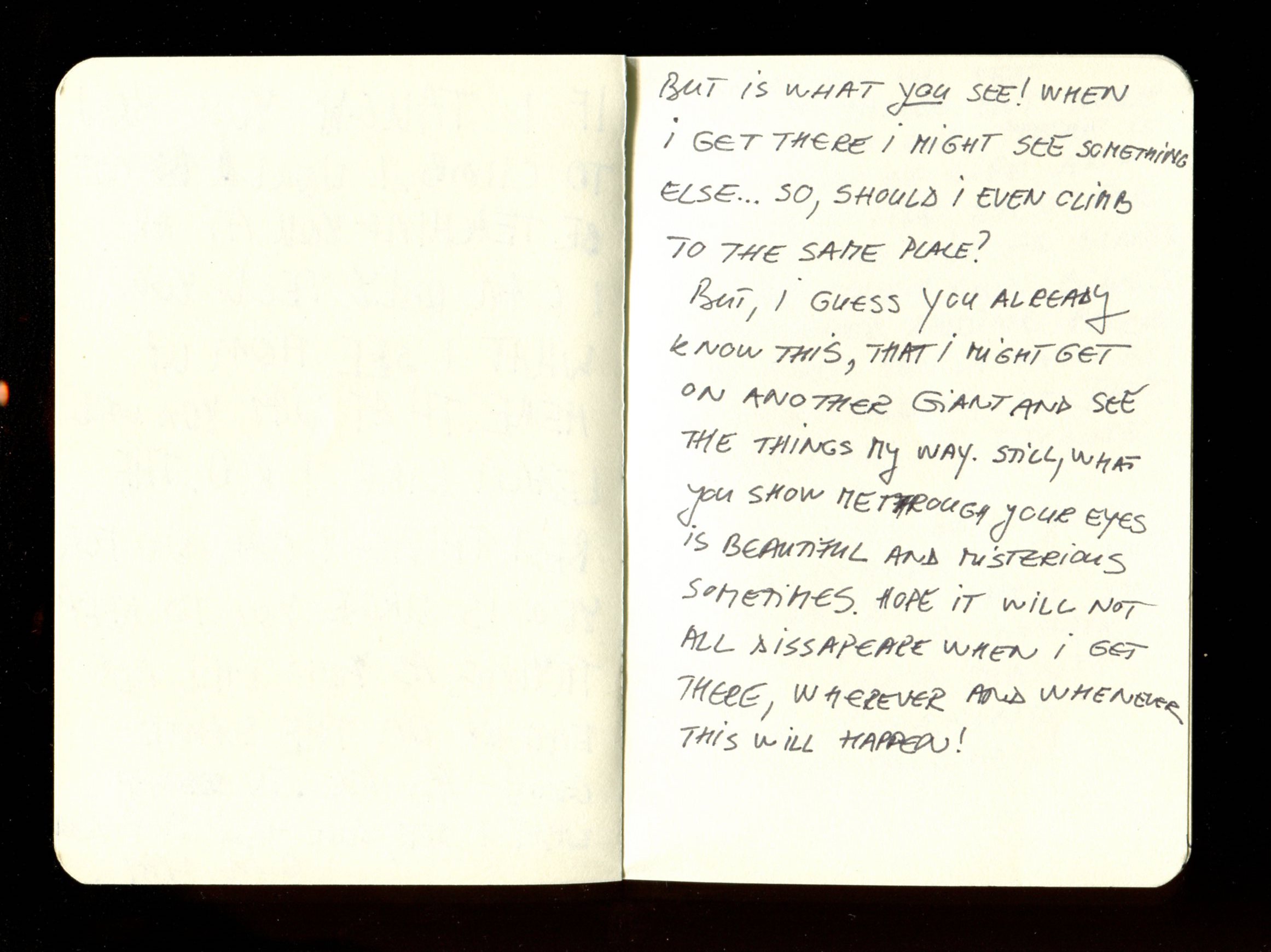

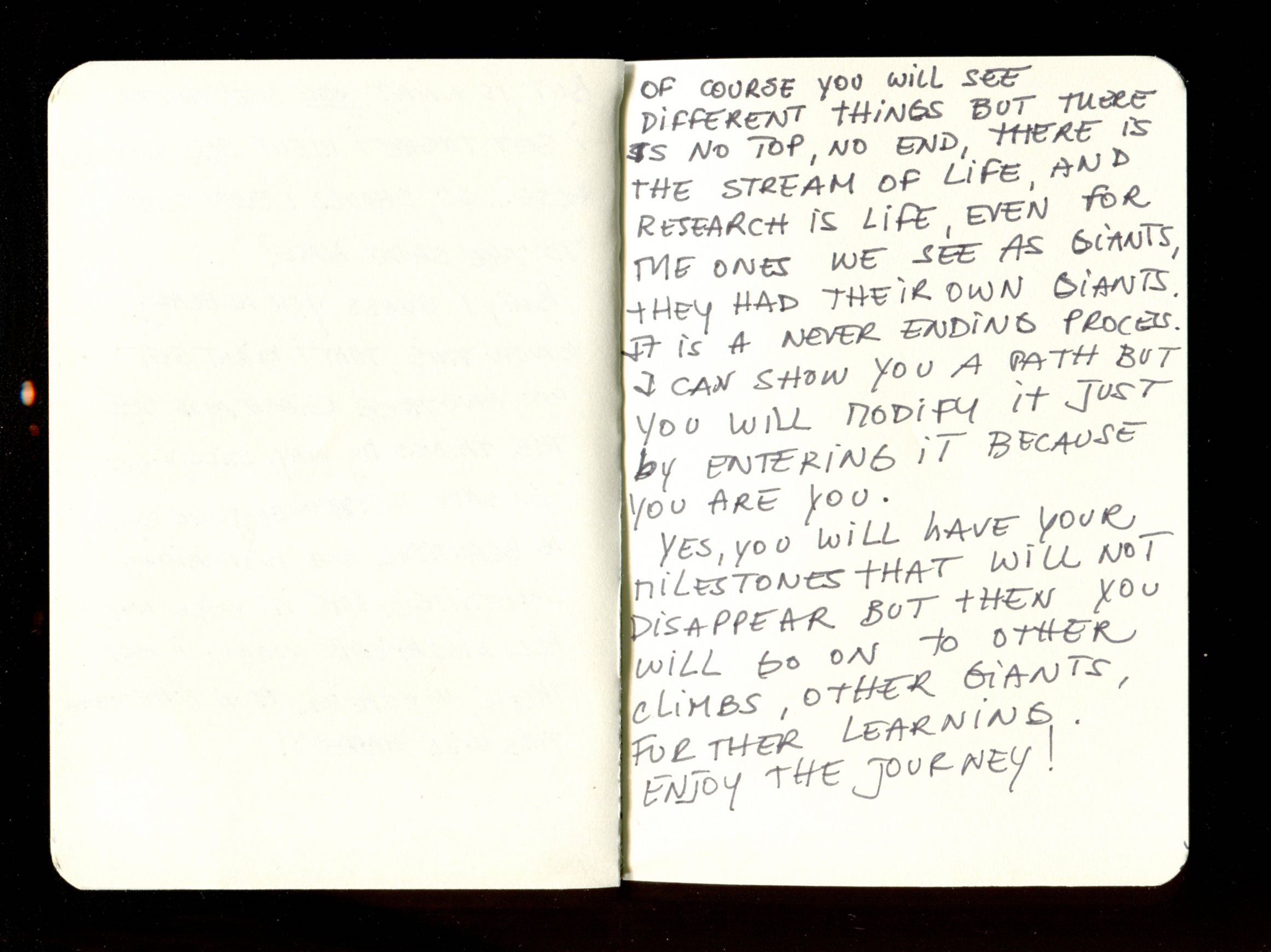

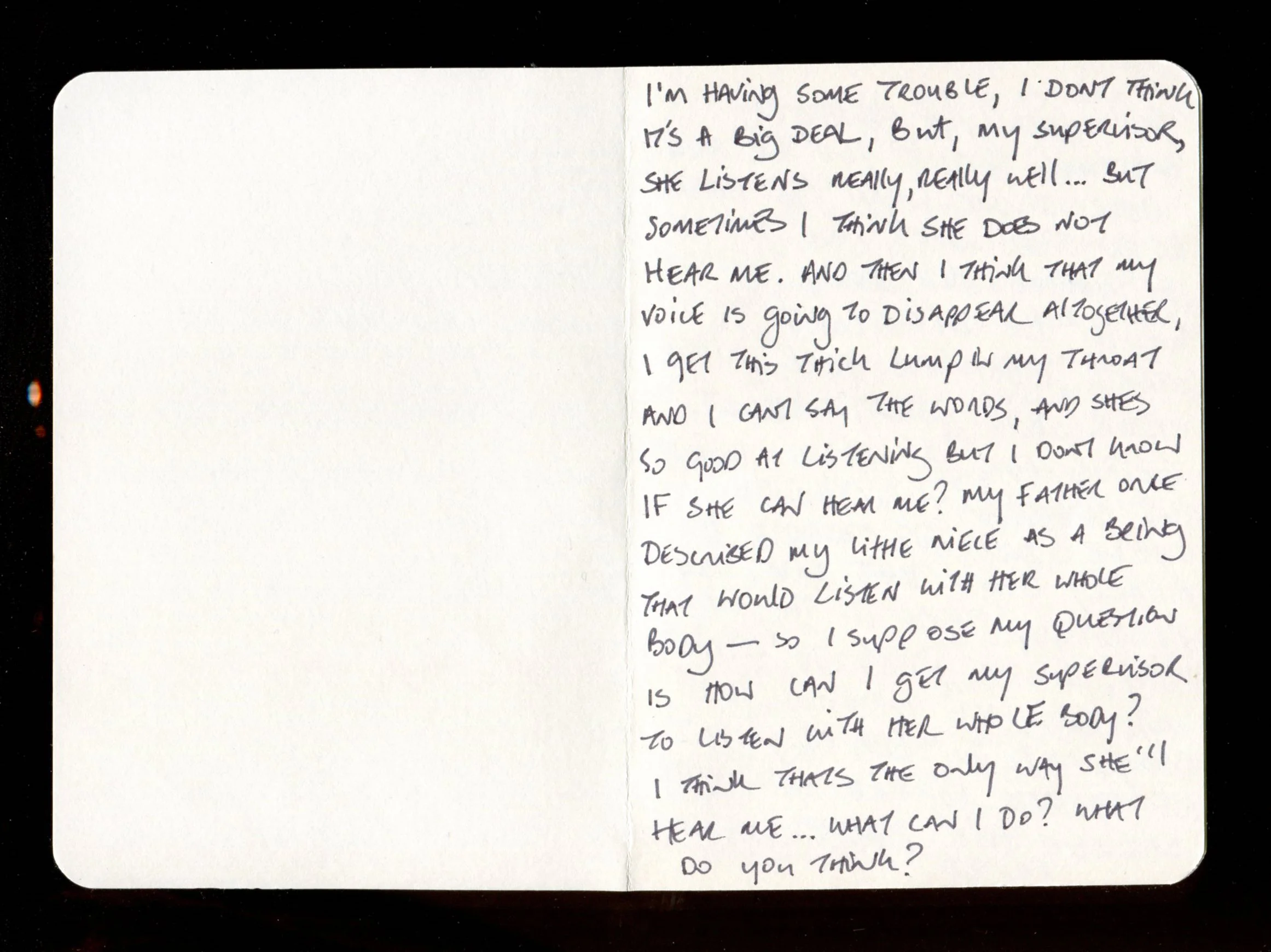

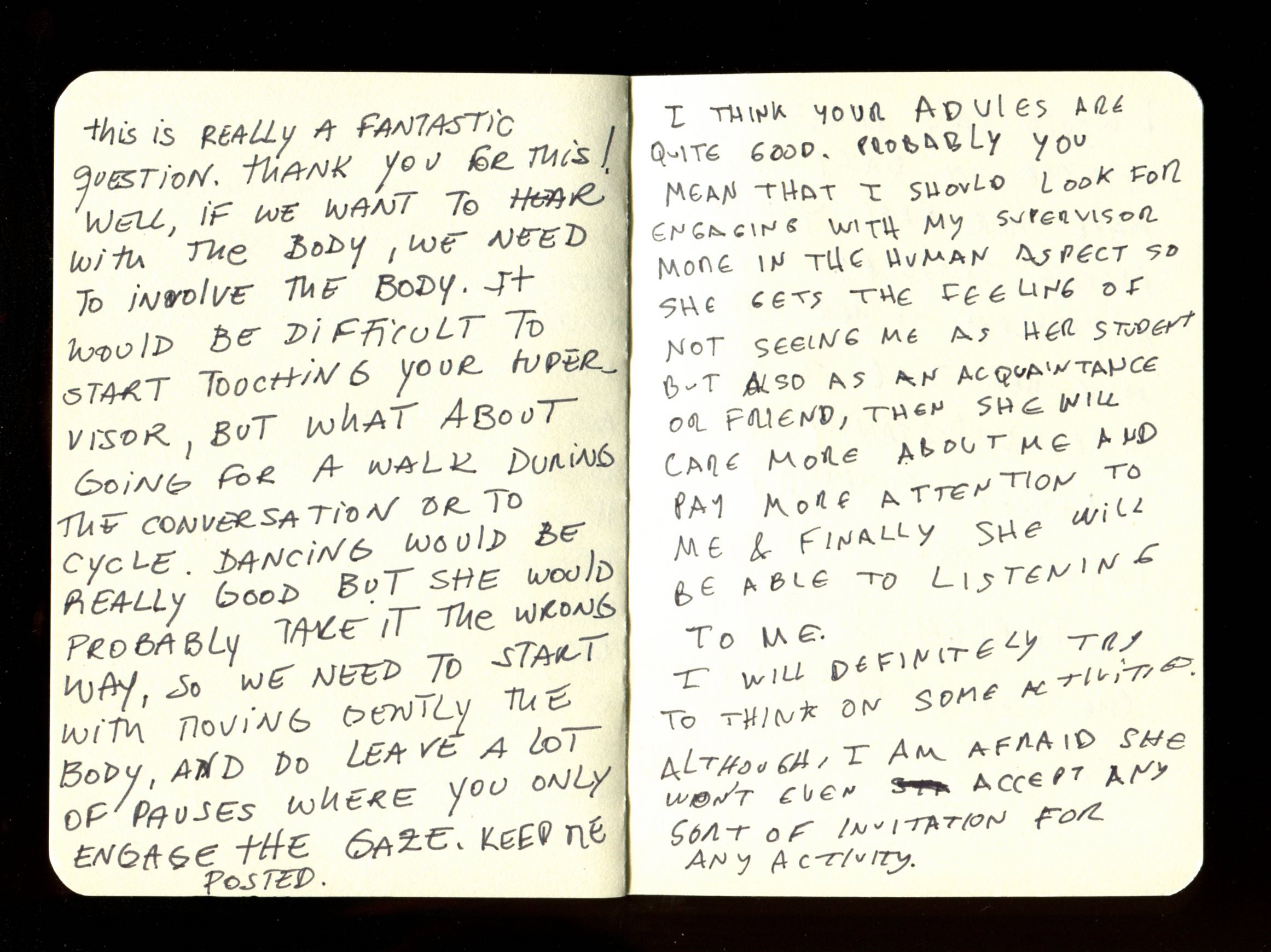

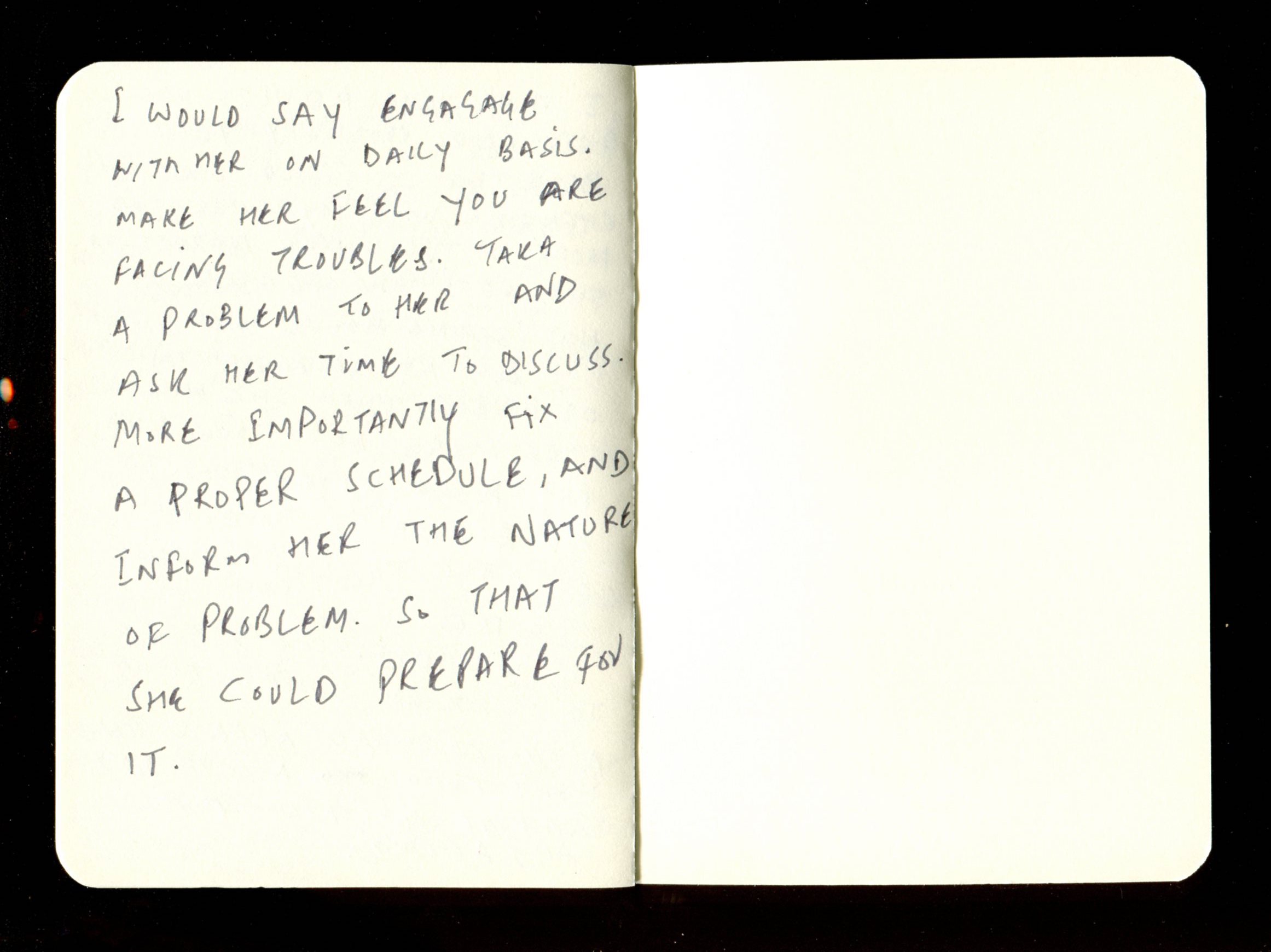

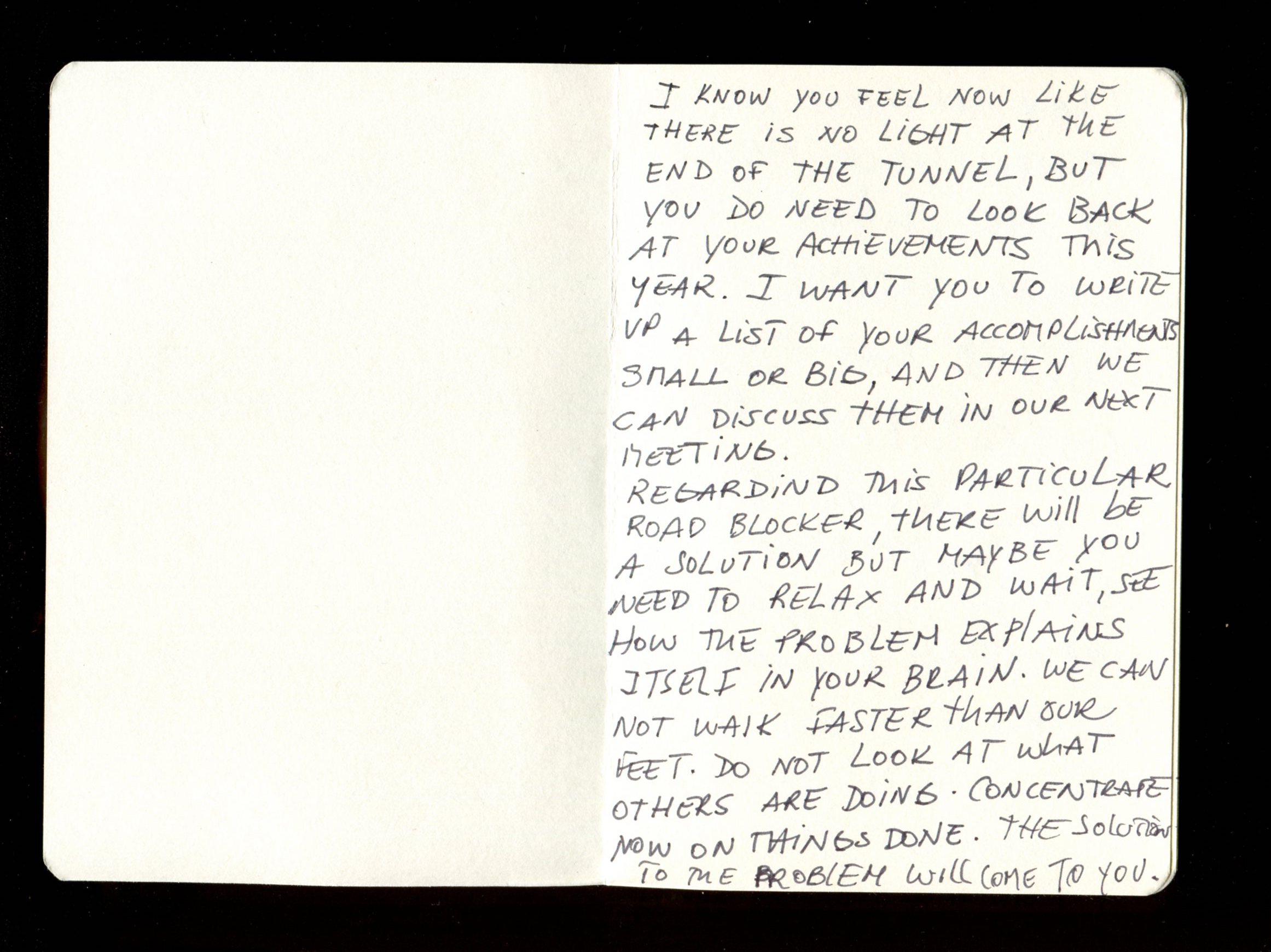

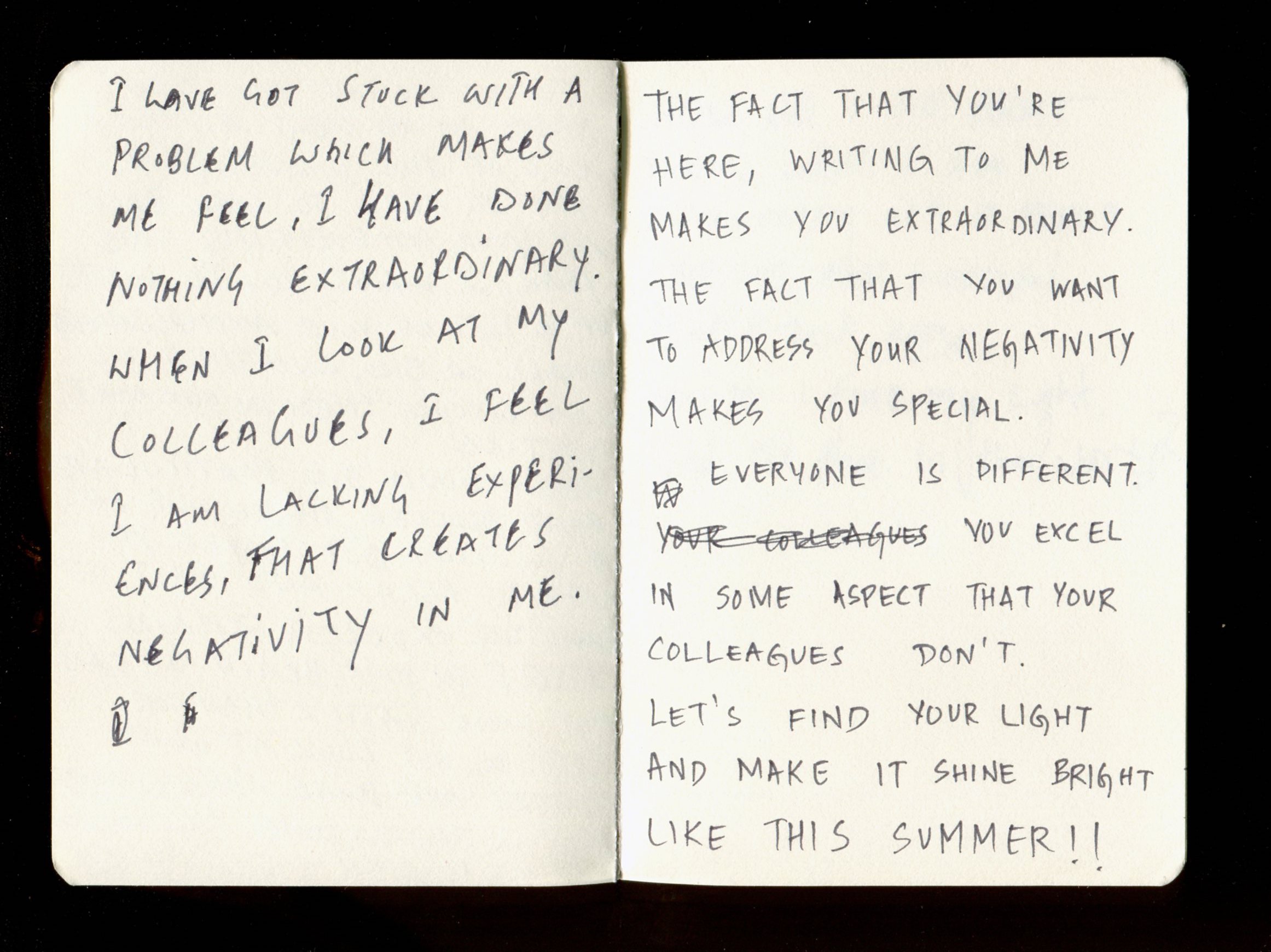

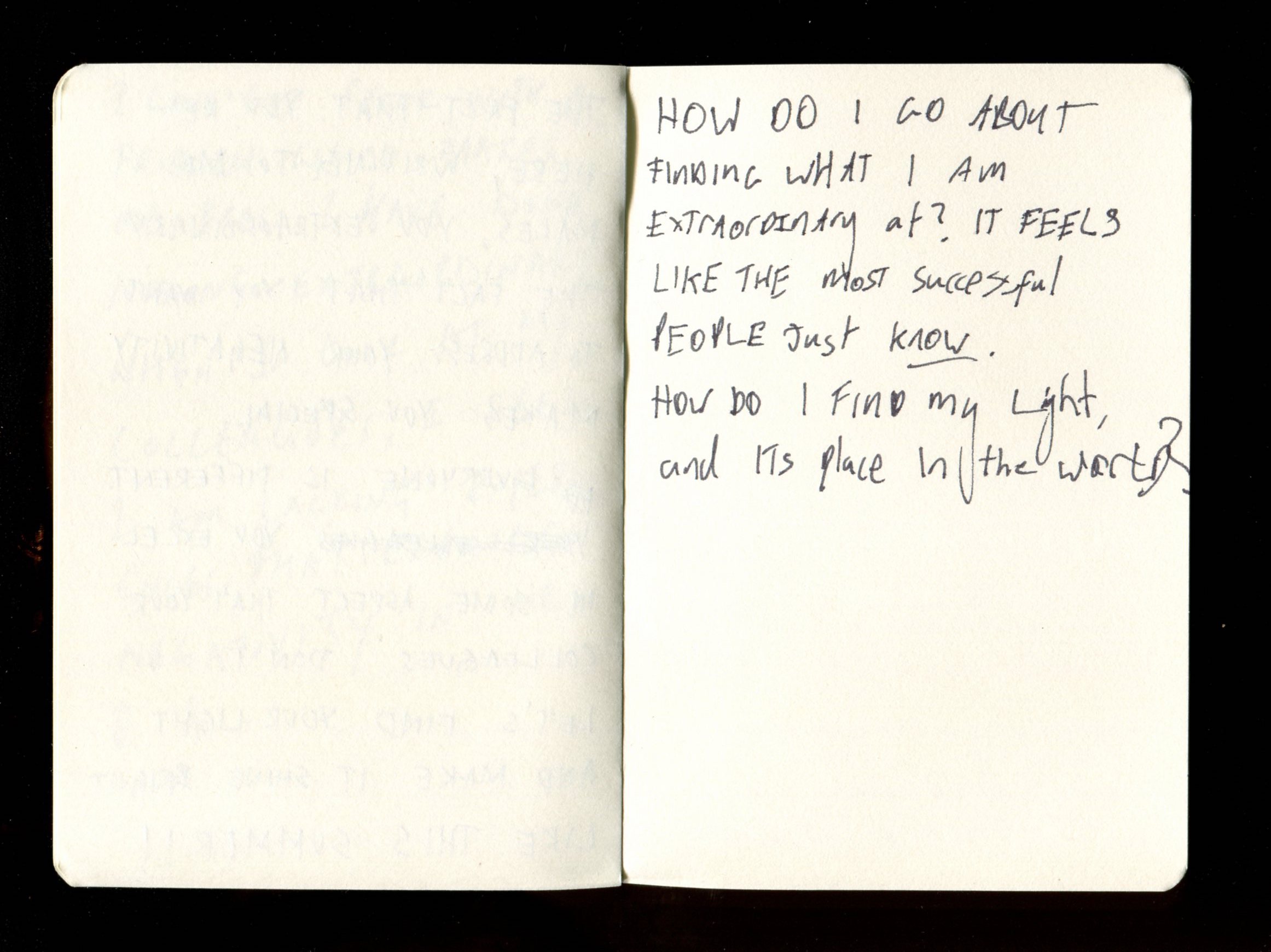

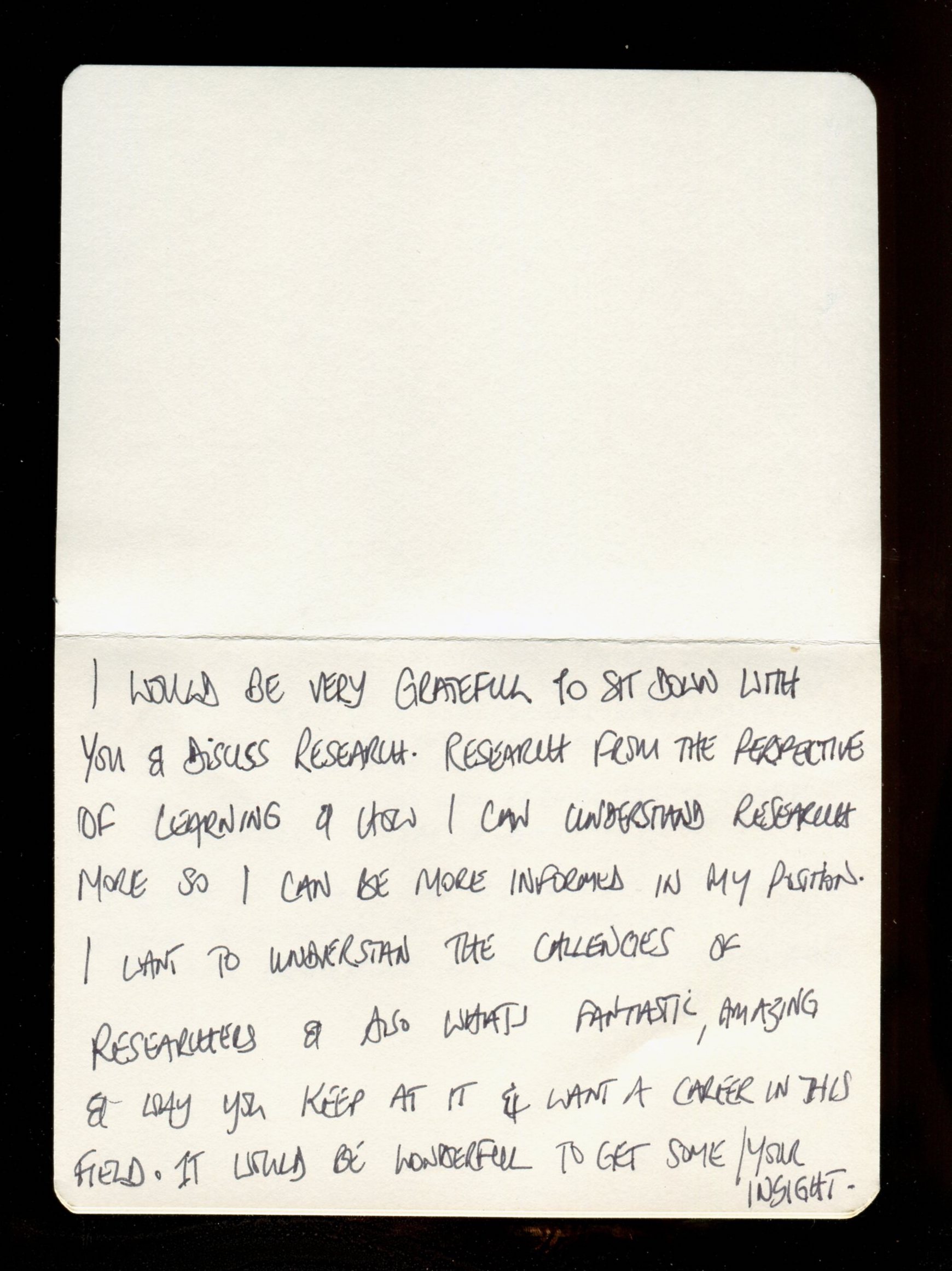

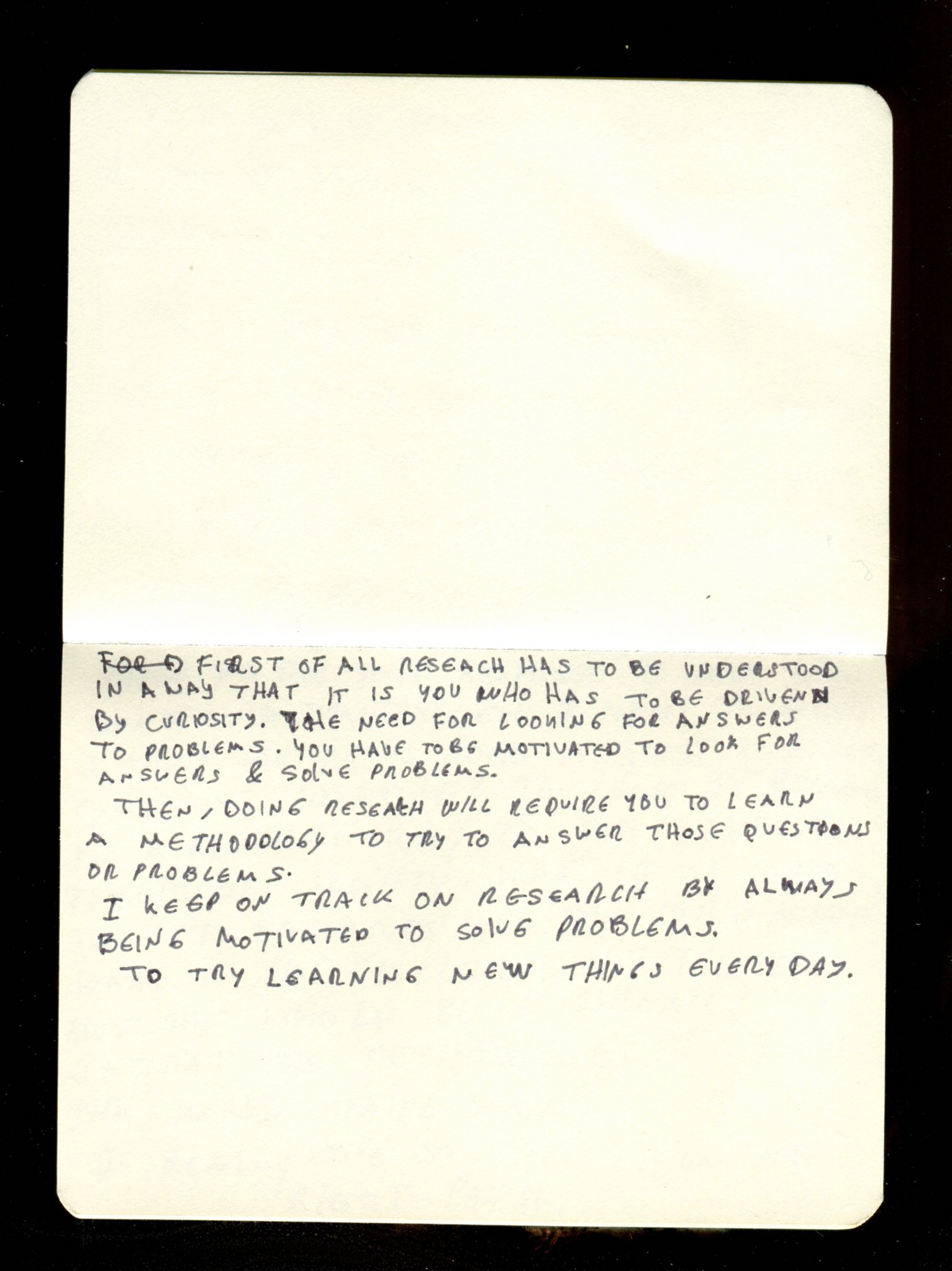

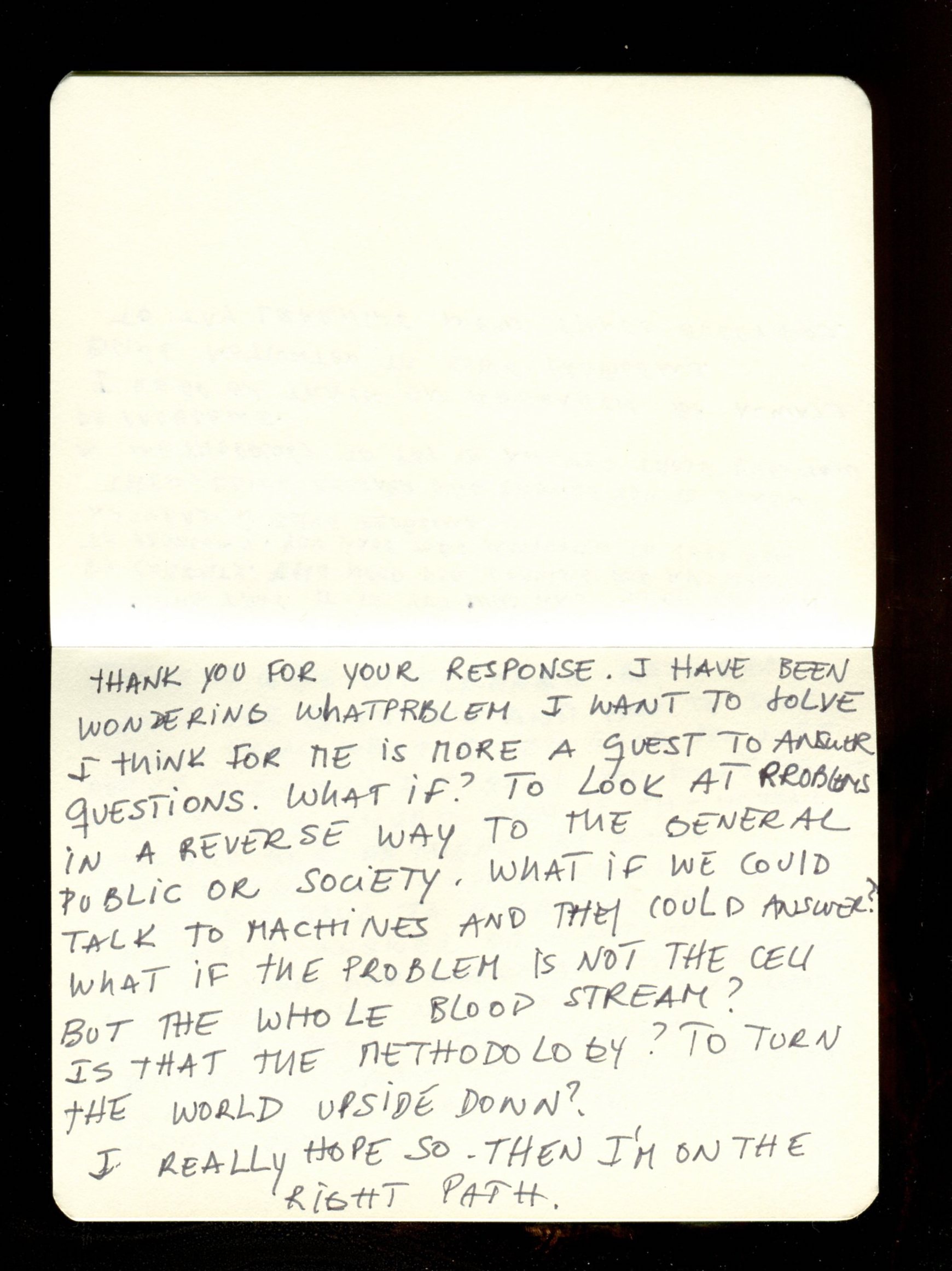

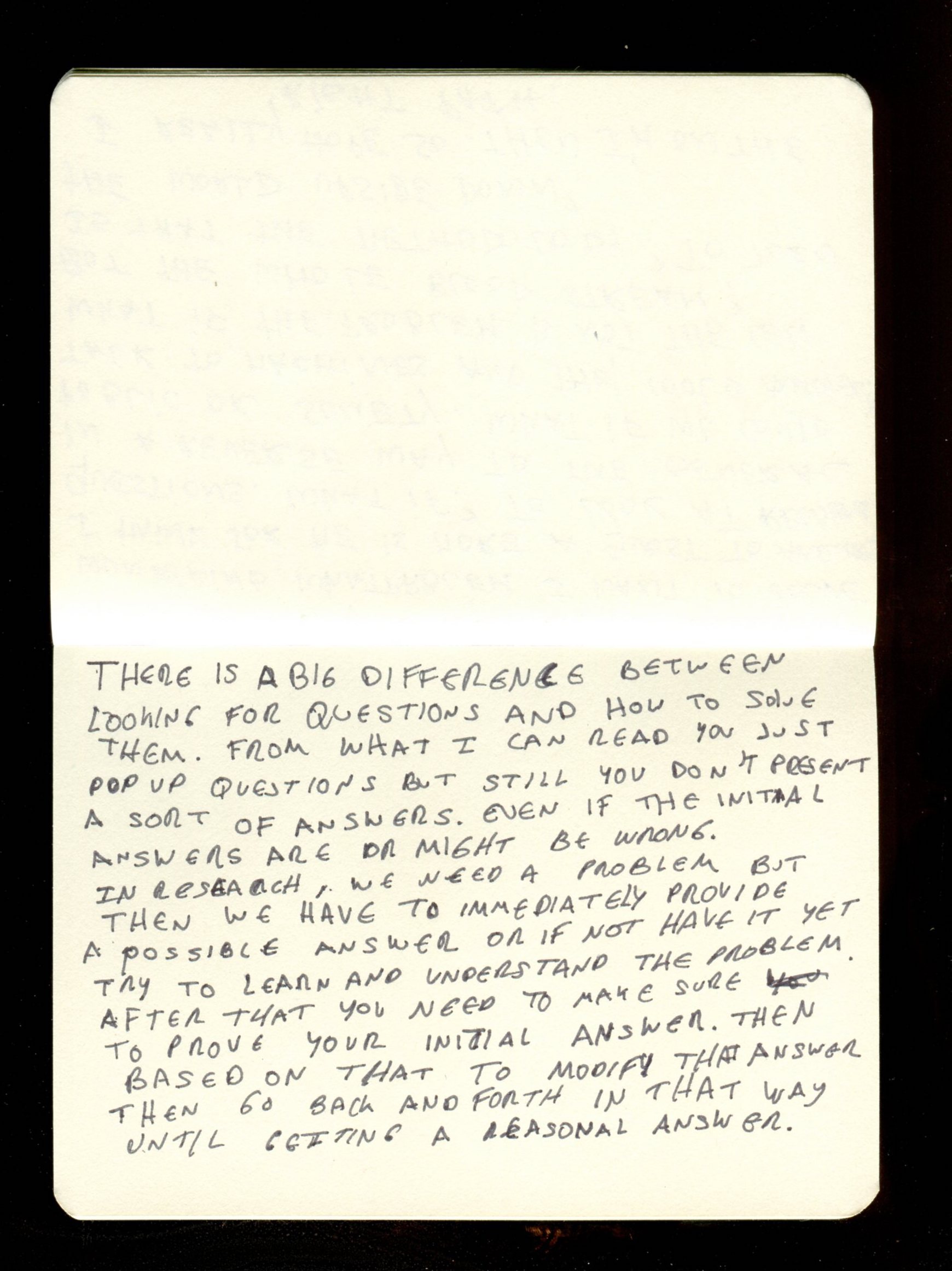

Stranger Fictions: Mentorship Writing Exercise

Everyone take a notebook and pen

Now, name and think about an issue that relates in some way to research life.

Think about this issue from the perspective of someone (a) giving advice or offering feedback OR (b) seeking listenership, advice and feedback. e.g. Decide if you will write as a Mentor or Mentee.

Decide whether you will assume a particular status as this person (peer/superior/subordinate?)

Write in BLOCK CAPITALS on ONE page as someone (a) giving advice/feedback or (b) seeking or receiving advice/feedback.

When you have filled the page (more or less) place your notebook in the centre of the table and choose another. Take it that the text on the page is addressed to you and respond accordingly.

Repeat this process for a limited period of time (e.g. 20-30mins)

Once finished writing, pair up and read aloud the correspondence from the notebooks.

Spells are poems; poetry is spelling. Spell-poems are vehicles of change that take us beyond the borders of the rational into a place where the right words can influence the universe.

Sarah Shin and Rebecca Tamás, Spells: 21st century occult poetry